Buzzkill

Drone operations in the Russo-Ukrainian War, 2025

Before she sank, the flagship of Russia's Navy loomed large over the Black Sea. Finished in early 2003, the Moskva battleship was packed with sensors, radio jammers and cannons to sense and repel any type of attack. She had batteries of S-300F and OSA-MA missiles for long to medium range defense. The Moskva was also armed with six 30mm/AK-630 close-in weapon systems that have their own radar and are capable of detecting and engaging the incoming threats autonomously at short range. Moscow controlled commercial shipping lanes across the entire Black Sea and was positioned to pummel Ukrainian cities like Odessa with missiles.

Russia’s Ministry of Defense (MoD) claims the warship sank after an accidental fire detonated ammunition onboard. But footage of the damaged vessel, which emerged April 18th, seems to confirm Ukraine’s claim that it hit the ship with Neptune missiles. How could a country with no navy of their own possibly inflict such a significant naval loss?

Ukraine brilliantly outmaneuvered their opponent by using at least one unmanned aircraft, a TB2 drone, to confuse the air defenses on the mighty battleship. While the ships's radar was trained on the decoy drone, away from the coast, a pair of trucks briefly switched on their targeting radars and fired a Neptune missile each, then sped away. Hugging the curve of the Earth, the missiles flew low over the ocean before striking the Moskva's exposed P-1000 "Vulcan" anti-ship missiles and exploding.

The hybrid warfare tactics of using a relatively cheap drone to overwhelm traditional air defenses like those on the Moskva offer a glimpse of how future conflicts may be fought. From the heavily defended front lines where troops scout enemy armor and positions with quadcopters to the high-flying surveillance drones providing persistent surveillance of the battlefield below, the extensive use of drones by both sides makes the Russo-Ukrainian War the “first full-scale drone war.”

Choose your fighter

Aerial Surveillance Drones

Uncrewed aerial vehicles (UAVs), from small commercial quadcopters to larger, military level drones, are heavily used by both sides. They are designed primarily for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR).

Russia’s Orlan-10 is a fixed-wing reconnaissance drone with modular sensors (daylight cameras, thermal imagers, etc.) and even electronic warfare add-ons. It can fly for up to 18 hours and transmit data over 120 km, giving front line units real-time video and targeting data.

Ukraine and Russia also deploy countless commercial drones for short-range ISR. These inexpensive drones provide squad-level scouting and artillery spotting and have become ubiquitous on the battlefield. Many brigades now have dedicated drone reconnaissance units equipped with various ISR drones to locate enemy positions day or night.

Attack Drones

Combat and strike drones are armed UAVs capable of direct attacks with missiles or bombs. Ukraine’s Turkish-built Bayraktar TB2 exemplifies this category, famed for early-war strikes on Russian armor and artillery. The TB2 is a medium-altitude long-endurance (MALE) unmanned aerial vehicle that carries a payload of up to 150k g, including sensors and laser-guided bombs. With a 12 meter wingspan and 27-hour endurance, it can surveil and precisely strike targets at ranges of ~150 km.

TB2 drones performed surveillance and precision strikes in Syria, Libya, and Ukraine, demonstrating effectiveness against armored columns and even naval targets in the war’s first months. Russia’s counterparts include the Orion (Inokhodets) unmanned combat aerial vehicle (UCAV), which carries guided munitions, and the Iranian-made Mohajer-6 supplied to Russia (a smaller attack drone with ~200 km range and ability to drop bombs.

These strike drones provide a measure of air power on a drone-saturated front where manned attack aircraft are constrained by dense air defenses. They are used for hitting high-value targets like tanks, artillery, and command posts with precision munitions, often working in tandem with ISR drones that locate targets.

Naval Drones (Surface and Submersible)

Naval drones – uncrewed surface and underwater vessels – have opened a new front in this conflict. Ukraine pioneered the use of explosive uncrewed surface vessels (USVs): small, fast drone boats laden with explosives, directed via remote control toward Russian warships. These “suicide boats” can carry large explosive payloads and detonate at a ship’s waterline, posing a serious threat even to large vessels.

Notably, on , Ukraine launched a swarm of USVs and aerial drones against Russia’s Black Sea Fleet in Sevastopol – the first recorded multi-drone strike on a naval base. While that attack didn’t sink ships, it prompted Russia to bolster port defenses with booms, nets, and even trained dolphins. Continued Ukrainian naval drone strikes through 2023 (including hits on a landing ship and a tanker) forced the Russian Navy to relocate major units from Crimea to safer ports.

Both sides are also exploring underwater drones. Ukraine’s SBU security service has unveiled a new 6-meter unmanned underwater vehicle (UUV) project in 2023, and Russia has touted its experimental Poseidon nuclear-powered torpedo (though not deployed in this conflict). These naval drones extend the war to the maritime domain – performing surveillance, delivering ordnance, and even targeting strategic infrastructure like bridges.

Loitering Munitions (“Kamikaze Drones”)

Loitering munitions are one-way attack drones that cruise until they find a target and then dive in to detonate – essentially expendable “kamikaze” drones. Russia has employed several types extensively. The ZALA Lancet-3, for instance, is a propeller-driven loitering munition with a 40km range and a 3kg explosive warhead. Weighing only ~12kg, Lancets use electro-optical guidance to home in on armor or artillery and have destroyed dozens of howitzers, air defenses, and vehicles in Ukraine. Even smaller models and first-person-view (FPV) drones – often modified racing quadcopters carrying grenades – are used at the platoon level to dive-bomb trenches or equipment.

Russia’s largest loitering drones are the Iranian-made Shahed-136 (Russian designation “Geran-2”). The delta-wing Shahed-136 has an estimated range of 1,300–2,500km and carries about a 40–50 kg warhead, effectively making it a slow, low-flying cruise missile . Though noisy and relatively slow (around 185 km/h), Shaheds are cheap and have a low radar signature due to their small size and composite body. Russia has launched hundreds of Shaheds in mass waves to strike Ukrainian cities and infrastructure, exploiting their low cost to saturate air defenses.

Ukraine, too, has fielded loitering munitions: the US-supplied Switchblade 300/600 and Phoenix Ghost drones, which are smaller (~10km range for the Switchblade 300, ~40km for the Switchblade 600) and better suited for attacking personnel or light armor.

Ground drones

Uncrewed ground vehicles (UGVs) share the same purpose as uncrewed aircraft and loitering munitions: to keep humans out of harm's way while enabling them to complete their missions. UGVs have proven themselves in a variety of dangerous situations where maneuverability and absolute control are critical. These include disposal of explosive ordnance (EOD) and improvised explosive devices (IED), hazardous materials handling (HAZMAT), and special weapons and tactics (SWAT) team operations.

A promising area of ground-drone design is to transport wounded from the battlefield. "Communication with the military has shown us that the defenders suffer many of their losses during the evacuation of the wounded," says Nataliia Kushnerska, the head of Brave1, a Ukrainian government organization that helps to steer private inventions toward adoption by the country's military.

Kushnerska says a remotely controlled or autonomous vehicle could take the place of the three to six soldiers needed to carry a wounded soldier away from the front lines.

Specialized or Experimental Drone Platforms

Ukraine launched an “Army of Drones” initiative to train operators and develop swarms of small drones, and aims to produce up to 1 million FPV drones in 2024 to overwhelm Russian forces. Other innovations include cardboard drones: Australia’s SYPAQ has supplied flat-packed Corvo PPDS drones that Ukrainian forces use for reconnaissance and even light bombings – these cheap disposable UAVs fly 100+ km and can deliver supplies or explosives, demonstrating creative low-cost engineering. It's Google Cardboard for drones.

Both sides are also experimenting with drone swarming and AI. By late 2024, Russia reportedly began upgrading Shahed-136 drones with onboard AI for target recognition and navigation without GPS. While true autonomous swarms have not been seen in combat yet, Russia is “investing heavily” in the concept of AI-powered drone swarms.

Snipers in the sky

Both Ukraine and Russia have deeply integrated drones into their battlefield tactics. Reconnaissance and targeting is the foundational use: virtually every unit has access to live aerial surveillance. Small drones scout ahead of infantry and armor, identifying enemy positions and guiding troops. Medium UAVs orbit higher up to direct artillery fire – a practice so effective that Ukrainian gunners can often drop shells precisely on targets spotted by drones.

In one case, a Ukrainian officer located a platoon of Russian tanks with a drone and called in precision-guided artillery to destroy three tanks in two minutes. Drones have thus become indispensable eyes in the sky, enabling a coldly efficient “kill chain” where recon drones find targets and attack units (artillery or strike drones) swiftly engage them.

Loitering attack drones and FPVs are used at the tactical level to hit targets that hide from direct line of sight. Usually, a small quadcopter first pinpoints a target (like a tank in cover or a machine gun nest); then an FPV drone zips in at low altitude to crash into it. This coordination allows relatively cheap drones to take out high-value assets. Every day, both Ukrainian and Russian drone teams post combat footage of $500 hobby drones destroying million-dollar armored vehicles – a stark demonstration of the military imbalance introduced by affordable commodity hardware.

The dense concentration of air defenses at the front has largely grounded any manned attack aircraft, so drones fill the gap for close air support and precision strikes. Ukraine’s military has formally integrated drones into its ranks – by late 2023, almost every brigade had a dedicated “assault drone company,” and most combat units had organic reconnaissance drones. These drone units specialize in surveillance, artillery spotting, loitering strikes, and even “bombings” (quadcopters dropping grenades).

On a larger scale, operational-level strikes use drones for deep attacks and harassing the enemy’s rear. Russia’s strategy with Shahed drones is to launch them in swarms of a dozen or more, often at night, aiming to overload Ukrainian air defenses. These drones have two goals: destroy infrastructure like power stations, and consume Ukraine’s stock of costly surface-to-air missiles by forcing frequent interceptions. The Shaheds often fly circuitous routes to confuse radars and approach low, acting as decoys as much as weapons.

Meanwhile, Ukraine has developed long-range drones of its own to hit airbases, oil depots, and even Moscow. Starting in 2023, Ukrainian forces began striking military targets deep inside Russia (hundreds of kilometers from the front) using homebuilt UAVs with extended wings and increased fuel for range. Early attempts were frequently jammed by Russian electronic warfare, but Ukraine adapted and successfully hit sites like the Engels bomber airbase (damaging strategic bombers) and oil refineries in 2023. These long-range drones – models like the UJ-22 Airborne with an ~800 km range and other secret UAVs – serve a similar role to cruise missiles, extending Ukraine’s strike reach when missile stocks are limited.

Battlefield coordination has also evolved with drones. Commanders now routinely use drone feeds for real-time situational awareness. Drones orbiting above a battle can relay enemy movements to ground units and even direct infantry maneuvers (a sort of aerial battlefield Internet). Ukraine’s new “Drone Line” project is institutionalizing this integration: drone regiments and brigades are being scaled up and networked with infantry units to create 10–15 km deep “kill zones” covered by constant drone surveillance and strikes. The idea is to detect and destroy Russian forces before they can close with Ukrainian lines.

Ukrainian drone units remain somewhat separated to encourage rapid innovation, but they coordinate closely with conventional brigades. In contrast, Russia in late 2024 moved to centralize its drone operations under tighter military control, forming dedicated MoD-controlled drone regiments and pulling drone operators out of ad-hoc front line groups. This centralized approach aims to standardize drone support across units, though analysts warn it could slow the improvisation that made some Russian drone teams effective.

Drones are also used for propaganda and psychological operations. Both sides record strikes via drone cameras to publicize enemy losses. ISR drones have documented destruction (e.g., the leveling of Mariupol, or flooding from the Kakhovka dam breach) for information campaigns.

The mere presence of drones often forces troops to take cover or halt – Russian soldiers call the constant buzzing in the sky “an aerial patrol.” This persistent drone observation has changed tactics: units disperse more, use smoke or electronic jammers, and avoid moving in daytime if possible. In essence, drones have enforced a form of “battlefield transparency” where any movement risks detection and prompt attack.

There are clear signs that Ukraine is exploring automation, including for the ‘last mile’ of an attack where electronic warfare may interfere with communications

Technical Specifications and Capabilities

Bayraktar TB2 (Turkey/Ukraine) – Medium-altitude armed UAV with 27-hour endurance and 150 km control range. It carries 4 laser-guided bombs (total payload ~150 kg) and features advanced EO/IR sensors and laser designator for day-night targeting. The TB2 cruises around 120–130 km/h and can reach altitudes of 8,000+ m, but has a relatively low radar cross-section due to its small size. It is not a stealth platform, but its light composite build makes it harder to detect than manned aircraft. Triple-redundant avionics and autonomous takeoff/landing capability add to its reliability .

Orlan-10 (Russia) – A small fixed-wing ISR drone (max takeoff weight ~16.5 kg) with a gasoline engine. It has an 18-hour flight endurance and typical operational radius of 100–120 km from its ground station. The Orlan-10 carries a modular payload of up to ~5 kg, usually a gyro-stabilized daylight/IR camera and a radio transmitter. Some Orlan-10s can also deploy jamming transmitters to disrupt communications or even drop small anti-personnel munitions. It cruises around 110 km/h. Notably, Orlan’s components include many off-the-shelf electronics (western cameras, GPS, etc.), reflecting Russia’s improvised approach to drone production.

Shahed-136 “Geran-2” (Iran/Russia) – Delta-wing loitering munition with an estimated range of 1,500–2,000 km and a warhead of ~40 kg high explosive. It uses a simple two-stroke petrol engine (50hp) and cruises about 150–185 km/h. The drone’s delta planform and low-altitude flight profile give it a small radar signature and make detection challenging. Guidance is primarily via inertial/GPS, though recent versions may use terrain-matching vision to reduce GPS dependence. Costing as little as $20,000–$30,000 each, Shaheds are relatively unsophisticated but highly cost-effective for long-range strikes. Their primary limitation is accuracy (many miss or are shot down; under 10% hit rate reported), but Russia compensates with sheer numbers.

ZALA Lancet-3 (Russia) – Electric kamikaze drone with 40 km range and 40-minute endurance, top speed ~110 km/h. It weighs 12 kg and carries a 3 kg warhead (usually High-explosive fragmentation) . The Lancet has X-shaped wings and a TV guidance unit transmitting video until impact. It can dive on targets at up to ~300 km/h terminal speed , enough to destroy unarmored vehicles or damage tanks. Lancets are launched by catapult and can operate in swarms of two or three, but their radio-controlled guidance is susceptible to jamming. Still, their precision and low cost make them lethal against artillery and radar units at the front.

Switchblade 300/600 (US/Ukraine) – Man-portable loitering munitions provided to Ukraine. The Switchblade 300 is 2.5 kg with a 10 km range, 10-minute flight, carrying a small anti-personnel warhead. The larger Switchblade 600 (~54 kg launch weight) has a 40+ km range and 40 min endurance, carrying an anti-armor warhead (~3–4 kg). Both are tube-launched and use GPS+video guidance; the 600 can reach 185 km/h and has a “wave-off” capability to abort or re-engage targets. These one-way drones allow Ukrainian units to hit armored targets from a safe distance without needing traditional fire support.

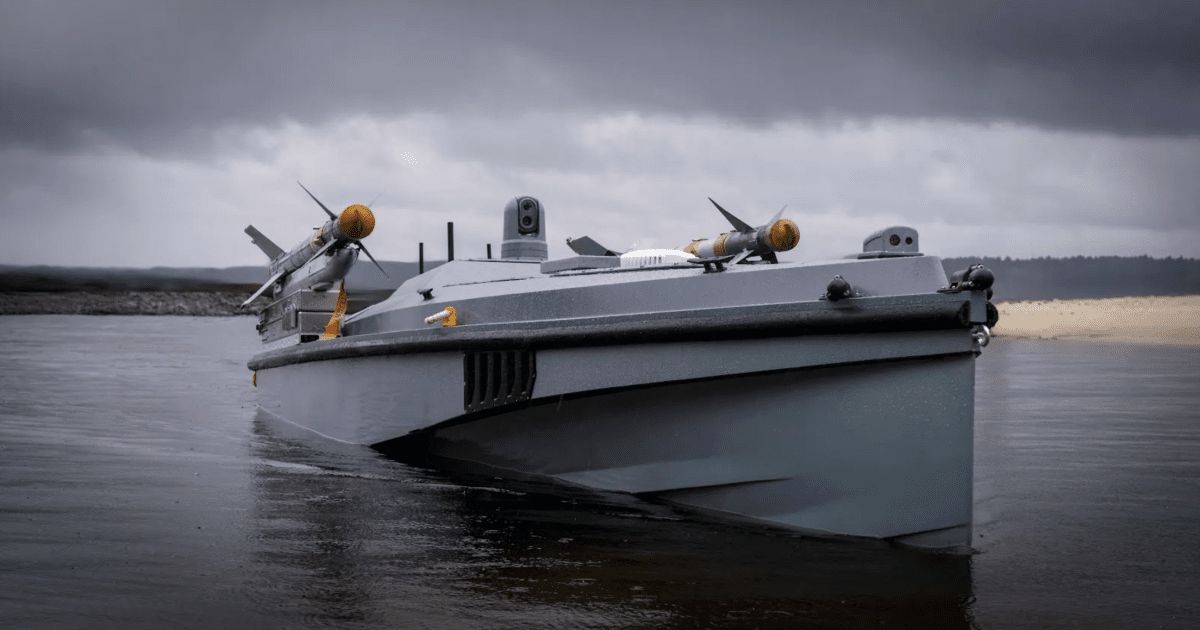

The Magura v5 is one of Ukraine’s most advanced drone boats. Back in May one was displayed with what was called a FrankenSAM arrangement: a pair of AA-11 Archer air-to-air missiles in an improvised surface launcher. The AA-11, known in Russia as R-73, is an infra-red, heat-seeking missile roughly equivalent to the U.S. AIM-9 Sidewinder. It is normally carried by jet fighters for dogfights, with a range of around 20 miles.

These USVs can approach targets at the waterline, where ship armor is thin, making even a single drone hit capable of mission-killing a warship. Such naval drones rely on remote control (or pre-programmed routes) and are designed to be hard to detect until final approach.

High-End NATO ISR Drones – While not directly armed in theater, NATO has flown large high-altitude drones (like the US RQ-4 Global Hawk) along Ukraine’s borders to collect intelligence. These craft have 30+ hour endurance, ceiling above 15 km, and sophisticated sensors (radar, SIGINT, optical) feeding information to Ukraine. A notable incident was the March 2023 encounter when a Russian fighter jet collided with a US MQ-9 Reaper drone over the Black Sea, highlighting the risk of these operations. Such Western UAVs provide strategic overwatch but do not cross into Ukrainian airspace (to avoid escalation).

Russian ZALA surveillance drones and Lancet-3 loitering munitions now routinely work together to find and destroy Ukrainian artillery. While military drones play important roles, commercial off-the-shelf drones, such as the Mavic series from DJI, are also omnipresent on the front lines. Swarms of FPV drones pick off any soldier unfortunate enough to be caught outside an armored vehicle.

Overall, the drones in this war cover the full spectrum: long-endurance ISR platforms, armed strike drones, kamikaze munitions, and novel naval drones. Advances in sensors (thermal imagers, laser designators), communications (satellite control, anti-jam systems), and even stealth shaping (as seen in the Shahed’s radar-evading shape) have all been battle-tested. This mix of range, payload, and capability allows drones to fulfill roles from tactical reconnaissance at a few kilometers to strategic strikes hundreds of kilometers away.

Fighting flight

Drones have had a transformative impact on operations in Ukraine, arguably shifting the balance of power in many engagements. A UK defense think-tank study found that by late 2024, “tactical drones are inflicting roughly two-thirds of Russian losses” in equipment. In other words, drones (combined with the strikes they enable) now account for 60–70% of Russian combat losses – making them more effective than all other Ukrainian weapons combined. This is a remarkable change, considering Ukraine had almost no drones in its inventory at the war’s start.

Constant drone surveillance and real-time intelligence has vastly improved artillery accuracy and responsiveness: Ukrainian forces have routinely destroyed high-value targets like ammo depots and command posts deep behind enemy lines by using drones to spot for HIMARS rocket strikes or tube artillery. In one notable incident, a Ukrainian drone-guided strike in July 2022 took out a Russian brigade’s forward command center, killing a general and staff – an operation that would have been far riskier without drones locating the target.

On the Russian side, drones have enabled effective counter-battery and anti-armor tactics. The Russian army’s widespread use of Lancet loitering munitions has destroyed a significant number of Ukrainian howitzers, self-propelled guns, and even several Western-supplied air defense systems. Videos confirm Lancets knocking out SA-8 and Strela-10 air defense vehicles, and damaging modern howitzers like the Polish Krab. These strikes have eroded Ukraine’s artillery and forced them to pull valuable assets farther from the front.

Russia’s Shahed drone campaign, while often aimed at civilian infrastructure, had notable military effects during the 2022–23 winter: repeated Shahed barrages managed to cripple around 40% of Ukraine’s power grid, straining rail logistics and air defense resources. Even though Ukraine intercepted the majority of inbound drones, the ones that penetrated caused power outages that hampered factory production and troop rail movements in the rear.

Moreover, Russia’s strategy of using $20k drones to make Ukraine fire expensive SAM missiles is an economic warfare success. Ukrainians were initially using $500k Buk or S-300 missiles to shoot down each Shahed. Ukraine has since adapted by using cheaper guns and machine guns on pickup trucks to shoot down drones, but the strain on their air defense network remains.

Drones have directly contributed to major battlefield victories. In the Battle of Snake Island (2022), Ukrainian TB2 drones systematically destroyed Russian air defenses and supply boats on the island, forcing a Russian retreat. During Ukraine’s Kharkiv offensive (Sept 2022), reconnaissance drones identified weak points and gaps in Russian lines, allowing armored units to break through with minimal resistance. Conversely, in Russia’s assault on Vuhledar (early 2023), Ukrainian drone observers spotted advancing Russian tank columns and guided precise artillery ambushes that decimated dozens of vehicles. In effect, any large force concentration has become nearly impossible to conceal from aerial drones, often leading to disastrous results if an advance is not meticulously planned with drone recon of its own.

At sea, Ukraine’s naval drones have achieved strategic effects disproportionate to their cost. While the October 2022 Sevastopol raid was just a warning shot, later USV attacks scored direct hits: for example, in July 2023 a Ukrainian drone boat struck the Russian landing ship Olenegorsky Gornyak in Novorossiysk harbor, badly damaging and listing the vessel.

These attacks, combined with missile strikes, led the Russian Navy to essentially withdraw its major units from Crimea. This dramatically reduced Russia’s ability to threaten Odesa or launch Kalibr cruise missiles from its ships. In effect, Ukraine established a deterrent zone with drones, something it could never have done with its small conventional navy.

Drones have essentially turned the battlefield into a fishbowl, where surprise maneuvers are rare – a defining change that has broken the offense-defense balance

Drone operations have also produced psychological and political effects. The sight of Russian cities under drone attack – such as the May 2023 Moscow drone strike that hit wealthy districts and prompted evacuations – brought the war home to the Russian populace and embarrassed the Kremlin. Though damage was minor, President Putin had to order improved capital air defenses and acknowledged the psychological impact of Ukraine’s long-range drones.

In Ukraine, the image of TB2 drones hunting invaders became a morale booster early in the war (immortalized in the popular “Bayraktar” song). Conversely, the persistent buzz of enemy drones overhead has been cited by soldiers as a top stress factor, contributing to fatigue and fear. Drones have essentially turned the battlefield into a fishbowl, where surprise maneuvers are rare – a defining change that military analysts say has “broken the offense-defense balance” in many tactical situations.

Drone Countermeasures

The ubiquity of drones in Ukraine has given rise to equally prolific countermeasures, both electronic and kinetic. Electronic warfare (EW) has proven the most effective defense against drones overall. Both sides blanket the front lines with jamming signals to interfere with drone controls and navigation. Russian forces deploy truck-mounted EW systems (like Pole-21, Krasukha, Zhitel) that can jam GPS over wide areas and sever the radio link of quadcopters and FPVs. Ukraine, aided by Western technology, also uses portable jammers and EW units (such as the Ukrainian Bukovel or US-supplied DroneDefender) to force down Orlan-10s and other Russian UAVs.

When a drone’s control signal is jammed, it may crash or lose its video feed, neutralizing its usefulness. Specialized software-defined radios are used to detect and pinpoint drone frequencies, allowing operators to target them with directional jammers. In some cases, drones have been hijacked via cyber means – Ukrainian operators have exploited protocol vulnerabilities to take control of Russian commercial drones and land them. However, advanced military drones are usually hardened against such interceptions by using encryption.

On the kinetic side, a variety of air defense weapons are employed against drones. Traditional surface-to-air missile (SAM) systems like the Buk-M1, S-300, Osa, and even MANPADS have racked up scores of drone kills, especially against larger UAVs (TB2s, Orlans) and fast kamikaze drones. Russia claimed to have shot down over 100 Bayraktar TB2s by mid-2023 (likely an exaggeration), but many were indeed downed by Pantsir-S1 guns and missiles. The downside is cost: using a pricey SAM on a small drone is inefficient.

Thus, both sides increasingly rely on cheaper anti-drone weapons. Ukrainian forces mount heavy machine guns and anti-aircraft cannons (such as old ZU-23-2 twin guns) on vehicles, nicknamed “mobile flak wagons,” to shoot down Shaheds and low-flying UAVs. Autocannons like the German Gepard have been extremely useful, achieving high success against Shahed swarms with radar-guided 35mm fire. For soldier-portable defense, anti-drone rifles and jammers are used. These look like bulky rifles that shoot directed RF energy to jam or disrupt a drone. Ukraine has received systems like the Lithuanian SkyWiper and Polish Thunderbolt to equip front line units. There are even reports of Ukrainian snipers training to shoot down small drones with rifles when feasible.

Electronic vs kinetic methods each have strengths. EW can disable or drive off many drones at once without expending ammunition, but high-end drones have started incorporating anti-jam features or autonomous modes to resist jamming. Kinetic defenses (guns, missiles) physically destroy drones but can be overwhelmed by large numbers or decoys. In practice, an integrated approach is used: layered defenses where EW first attempts to jam the drones, and any that get through are engaged by guns or missiles. In urban areas, Ukraine has set up shotgun-armed UAV interceptors and even trained raptors (eagles) earlier in the war to snatch small drones – though the latter proved impractical at scale.

Both sides are now exploring emerging counter-drone technologies. These include high-powered lasers to blind or burn drones (Russia claims to have tested a laser system called “Zadira” against UAVs), and microwave weapons that fry drone electronics over a wide beam. Another field is anti-drone drones: small interceptor UAVs that can autonomously home in on enemy drones and collide with them. Ukraine has used quadcopters dropping nets or tethered “drone catchers” to ensnare Russian drones near critical sites. Radar surveillance specifically tuned for slow, low-signature targets has been deployed around key infrastructure sites to improve detection of incoming drones. For instance, Ukraine received several “DroneShield” and RAFAEL Drone Dome systems from partners, which combine radar, EW, and kinetic interceptors in one package. As the conflict continues, we see a cat-and-mouse evolution – for every new drone or tactic, a countermeasure is developed in response.

One stark example is the Russian adaptation to naval drones: after suffering surprise boat-drone attacks, Russian forces installed physical barriers and booms at port entries and around the Kerch Bridge, and even positioned barges and oil slicks to complicate USV approach. They’ve painted warship decks in disruptive camouflage to confuse drone targeting. Similarly, to counter FPV drones, troops string up camouflage nets over trenches and vehicle hatches (some units cover tanks in chain-link fence or improvised netting to prematurely detonate incoming FPVs). None of these measures are foolproof, but they add layers of defense .

In summary, electronic countermeasures are the first line of defense against drones in Ukraine, often forcing drones to crash or abort. When EW fails or is unavailable, point-defense weapons from rifles to SAMs are used to shoot drones down. The conflict has essentially become a massive testing ground for counter-UAS tactics, yielding lessons on how to protect forces from the ever-present drone threat.

Manufacturing and Foreign Assistance

The drones in this war come from a mix of local production and foreign supply, with many international actors indirectly involved. Ukraine’s drone fleet is a patchwork of domestic designs and donated systems from NATO partners. Before the invasion, Ukraine had only a handful of TB2s from Turkey and some reconnaissance drones like the Leleka-100 and Spectator made by local firms.

As the war progressed, Ukraine launched a crash program to build or procure drones en masse. Dozens of Ukrainian companies (often crowdfunded startups) are now producing UAVs – from small grenade-dropping quadcopters to larger one-way attack drones. For instance, Ukrainian manufacturers have developed the “Beaver” (Bober) long-range strike drone believed to be behind some Moscow attacks, and the UJ-22 Airborne with 800 km of range for deep strikes. The government has streamlined import of components like controllers and cameras and funded R&D, treating drone production as vital as ammunition. By 2025, Ukraine aims to be producing thousands of drones per month domestically, including experimental types with AI and swarming capability.

Still, foreign assistance has been critical. Turkey’s Baykar firm supplied an estimated 50 Bayraktar TB2s to Ukraine (some purchased, some reportedly donated by Turkey or via Polish crowdfunding efforts) in 2022. The United States and NATO allies have provided large quantities of small tactical drones. As of early 2023, the U.S. alone had committed over 700 Switchblade loitering munitions and 1,800 Phoenix Ghost drones to Ukraine, as well as 15 ScanEagle recon drones and numerous RQ-20 Puma hand-launched UAVs.

The U.S., UK, and allies also delivered micro-drones like the Black Hornet, a tiny helicopter drone for reconnaissance inside buildings or trenches. Direct NATO military drone deployments in Ukraine have been limited (to avoid escalation), but NATO intelligence assets – including AWACS planes and Global Hawk drones – operate just outside Ukraine’s borders to feed situational data to Kyiv.

Russia’s drone inventory similarly combines domestic and imported tech. Iranian support has been a game-changer for Russia: since August 2022, Iran has delivered hundreds of Shahed-136/131 drones and Mohajer-6 UAVs, plugging a gap in Russia’s long-range strike capabilities. Iran also sent technicians to help Russia set up local production – by 2023, Russia established a plant to manufacture Shahed derivatives (renamed Geran-2) on its soil.

Apart from Iran, Russia has likely sourced components from China’s commercial drone market. Despite export controls, Russian entities still acquire Chinese DJI drones and hobby parts through third parties, which are then converted for military use. Many Russian surveillance drones, like the Orlan-10 or ZALA models, were found to contain Western-made electronics. GPS modules, altimeters, and cameras from the US, EU, and Japan inside downed drones indicate a reliance on global supply chains. Sanctions since 2022 have tried to choke off this flow, but black markets and dual-use loopholes persist.

Key Russian drone makers include Kalashnikov’s ZALA Aero (which produces the Lancet and Kub loitering drones) and Kronshtadt (maker of the Orion armed drone). These firms ramped up output with state backing. President Putin ordered a dramatic increase in domestic drone production in 2023, aiming to equip military units with thousands of drones from mini quadcopters to heavy combat UAVs. By late 2024, Russia was reportedly eliminating bureaucratic hurdles for private drone developers to supply the army, even as the Defense Ministry consolidated control over procurement.

Despite these efforts, Russia still lags in small drone supply to troops. Reports suggest many front line Russian units rely on volunteer or crowd-sourced commercial drones due to supply chain shortfalls.

Western defense companies have indirectly been drawn in. Turkish firm Baykar gained international recognition (and more orders) after the TB2’s performance in Ukraine. American companies like AeroVironment (Switchblade’s maker) and Skydio (which donated reconnaissance quadcopters) have their products in active use by Ukrainian forces. Similarly, the Polish WB Electronics supplied some of its Warmate loitering munitions early in the war, and the Czechs provided the Primoco recon drones.

These contributions often come via military aid packages. In one notable case, an Australian company, SYPAQ, supplies cardboard drones (Corvo PPDS) to Ukraine – an innovative foreign assist that provides 100 low-cost drones per month for reconnaissance and supply delivery.

Finally, international training and support accompany the hardware. Ukrainian drone pilots have been trained by NATO experts on advanced tactics, and information sharing networks help Ukrainian operators get satellite imagery or electronic intelligence to cue their drones. Russia, too, has received Iranian training for Shahed usage and possibly advice from Chinese tech experts on electronic warfare.

This war’s drone dimension is truly global: parts made in Asia, weapons designed in the Middle East, funded by the West, assembled locally – all converging on the battlefields of Ukraine. Such foreign assistance and sourcing underscore how modern conflicts blur the lines between local industry and globalized arms supply.

Timeline of notable incidents

-

Feb 24, 2022

Ukraine’s small fleet of Bayraktar TB2 drones achieves early fame by ambushing Russian ground convoys. TB2s destroyed dozens of armored vehicles and SAM systems in the Kyiv and Kharkiv sectors, slowing Russia’s advance. In one strike, a TB2 eliminated a whole artillery battery and fuel trucks, footage that went viral and boosted Ukrainian morale.

(Sources: Ukrainian General Staff briefings, video evidence)

-

April 2022

In the Black Sea, a Bayraktar TB2 helps target the Russian flagship Moskva. Ukrainian officials hinted a TB2 was used to distract the ship’s air defenses while Neptune missiles were fired, contributing to the sinking of Russia’s flagship. Around the same time, TB2s operating from Odesa sank two Russian Raptor patrol boats near Snake Island. These incidents showcased drones augmenting Ukraine’s anti-ship capabilities.

-

29 Oct 2022

Ukraine launches a surprise drone swarm attack on the Sevastopol naval base. Six or more USVs and several aerial drones penetrated port defenses, damaging at least one minesweeper. Although no ship was sunk, this marked the first recorded multi-domain drone attack on a fleet in harbor, prompting Russia to greatly reinforce harbor defenses (booms, nets, armed dolphins) and adopt a more defensive naval posture.

-

Oct–Dec 2022

Russia begins large-scale use of Iranian Shahed-136 drones to bombard Ukrainian cities. Waves of Shaheds (often 20+ at a time) struck power plants and grid nodes from October onward. On some nights up to ~45 drones were launched, causing widespread blackouts as even a 10% leak-through rate meant critical hits. Ukraine adapted by improving multi-layered air defenses, but the campaign revealed the drones’ “swarm effect” in exhausting defensive missiles. This period also saw Ukraine innovate stopgap defenses like converting pickup trucks with AA guns to counter Shaheds.

-

5 Dec 2022

In a bold long-range operation, Ukrainian forces used a Tu-141 Strizh drone (a repurposed Soviet recon drone turned cruise missile) to attack Engels Air Base, 600 km inside Russia. The strike damaged two Tu-95 strategic bombers on the tarmac and killed three personnel, according to Ukrainian and Russian reports. This was one of the first hits on Russia’s nuclear-capable bomber fleet and demonstrated Ukraine’s ability to project force deep into Russia via drones. A follow-up drone attack occurred on 26 Dec 2022 at the same base, causing additional casualties.

-

May 2023

For the first time in the war, the Russian capital Moscow was targeted by a swarm of drones. On 30 May 2023, about 8–25 drones (the count disputed) flew into Moscow’s airspace. Several were shot down or jammed, but a few struck residential buildings in upscale areas, causing minor damage and two injuries.

While Ukraine did not claim responsibility, this incident had high symbolic impact – it proved that even Moscow was no longer immune, ushering in a new psychological phase of the war. Putin acknowledged it as Ukraine’s biggest drone strike on Moscow and ordered improved local air defenses. Sporadic drone raids on Moscow and other Russian cities (Tula, Pskov, etc.) have continued since.

-

Summer 2023

During Ukraine’s summer counteroffensive, drones were integral in reconnaissance for breaching Russian lines in Zaporizhzhia. At the same time, Ukraine ramped up naval drone attacks. On 17 July 2023, maritime drones packed with explosives were used in an attack on the Kerch Bridge linking Crimea to Russia, damaging roadway sections (confirmed by Security Service of Ukraine). In August 2023, a coordinated drone boat and missile strike at Novorossiysk harbor disabled the landing ship Olenegorsky Gornyak and forced Russia to temporarily halt naval operations there. These incidents underscore Ukraine’s innovative use of drones to strike strategic targets that were previously unassailable.

-

September 2023

A major Ukrainian attack on Sevastopol involved Storm Shadow cruise missiles hitting a shipyard drydock – but also likely reconnaissance or decoy drones aiding the strike. The attack destroyed a Kilo-class submarine and a large amphibious ship undergoing repairs, a severe blow to the Black Sea Fleet. Drones were reportedly used to confuse air defenses during the missile ingress. This combined operation showcased the synergy of drones with Western-provided precision missiles.

-

December 31, 2024

On December 31st, 2024, soldiers of the special unit of the GUR of the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine “Group 13” for the first time in history hit an air target using a Magura V5 naval strike drone equipped with missile weapons. During a dramatic battle (posted to YouTube, of course) in the Black Sea near Cape Tarkhankut in temporarily occupied Crimea, a Russian Mi-8 helicopter was destroyed by the use of R-73 “SeeDragon” missiles.

-

February 14, 2025

On 14 February 2025, an unmanned aerial vehicle hit the New Safe Confinement structure at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. The attack resulted in significant damage to the protective shelter, but did not lead to increased radiation levels in the surrounding area. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said that a Russian combat drone carrying a "high-explosive warhead" had struck the structure. Russia denied the allegations, instead suggesting that Ukrainian officials made the claim to disrupt peace negotiations.

-

Late 2024

Facing battlefield stalemate, Russia dramatically increased its use of one-way drones. Between September and December 2024, Russia launched more loitering drones (mostly Shaheds) at Ukraine than in the previous 23 months combined. At the same time, Ukrainian sources revealed Russia had begun integrating AI-based navigation and targeting in some Shaheds to improve their success rate . While not true autonomous swarms yet, this points to drones becoming even more sophisticated. Ukraine has responded by accelerating its own drone production and deploying “counter-swarm” tactics learned over months of defending against mass attacks.

Each of these examples highlights a different facet of drone warfare in Ukraine – from tactical strikes and anti-armor work to strategic bombardment and naval innovation. Drones have repeatedly delivered results that shaped the course of operations: blunting offensives, enabling surprise attacks, and imposing new costs on the adversary. As of 2025, drones are central to the conflict’s conduct, and any significant operation is virtually guaranteed to involve a drone element on one or both sides.

Drones have indeed transformed the battlefield in Ukraine by providing accessible and affordable capabilities at a scale that did not previously exist. They are making it difficult to concentrate forces, achieve surprise, and conduct offensive operations. While drones are not more survivable than crewed aircraft, they enable greater risk acceptance. Moreover, drones do not have to be survivable if they are cheap and plentiful as they can achieve resiliency by reconstitution.

Still, the overall impact of drones has been more evolutionary than revolutionary. Drones connected to ground-based fires units have made common artillery shells precision weapons. First-person-view kamikaze drones can accurately hit mobile targets, making the front lines even more lethal. Nevertheless, even large numbers of small drones cannot match the potency or volume of artillery fire and thus cannot substitute for howitzers. Also, while drones provide affordable airpower, they have not replaced traditional air forces, nor have they been able to obtain air superiority. With this in mind, Washington should continue helping Ukraine improve its drone fleet, while being realistic about the impact this will have.