TL;DR

- GTA V relentlessly satirizes American society and the American Dream via in-game billboards, radio advertising, and missions that parody real-life issues and brands.

- The deeply satirical environment can be interpreted as a modern "satirical play" with the detailed game world acting as the stage, the characters providing the storyline, and the player's actions driving the narrative.

- Since its launch a decade ago, GTA V has generated $5.2 billion in digital revenues and $3.1 billion in physical sales. GTA VI, expected in May 2026, is projected to generate $2.7 billion at launch as the franchise returns to Miami.

Grand Theft Auto is one of the most successful entertainment products in history. With global sales of the game surpassing 215 million units as of May 2025, the cultural impact of Rockstar Games' series rivals that of Disney’s Mickey Mouse and George Lucas’ Star Wars. Unlike the wholesome narratives typical of Disney programming, however, Rockstar Studios offers a mature, borderline sadistic, perspective on the American experience.

What drives sales like these? With so many new games coming out every month, what is so intriguing about this series that keeps players engaged? The answer is multi-faceted, and reveals much about the evolution of gaming and how a video game can become a powerful tool of artistic expression.

British-founded Rockstar Games delights in exploring what is means to be American. Alongside other franchises like LA Noire (2011) and Red Dead Redemption (2004+), Grand Theft Auto (1997+) is fundamentally an exploration of North American geography and culture. Critical commentary about America is delivered through detailed environmental immersion, character narrative, and mission-based play.

Radio stations and billboard advertising in GTA V are used to advertise various in-game products, services, and even fictional political campaigns. These ads enhance the game's lively, dynamic city atmosphere and help define "Rockstar's America." As the story progresses, and as revealed in psychotherapy sessions, the game's characters develop further. The final section of this article explores the reasons for the game's financial success and provides a glimpse into what we might expect from GTA VI.

GTA V lifetime unit sales, worldwide

California screamin'

GTA V is a sprawling tale of three criminal maniacs self-destructing in a blood-splattered spree from one crisis to another. Michael De Santa is a middle-aged thug, obsessed with movies, who is living a comfortable life undercover after a deal brokered with the feds. When his old partner Trevor Philips, a sociopath who cooks meth out in the desert, re-enters his life, the two join forces with a young Black kid, Franklin Clinton, who's set on leaving his gang-infested neighborhood behind.

On its release in 2013, journalist Keith Stuart described GTA V as “a freewheeling, nihilistic satire on western society” and a “monstrous parody of modern life”, while politician Tom Watson labeled the game “a giant, targeted missile of satire”. The contribution of dark humor is widely credited for the game’s success. Kiri Miller notes how the series “appeals to players attuned to political parody and popular culture,” allowing players to perform violent acts in the game but see them as distant, fake, and ironic.

Modeled on Los Angeles, the digital landscape of Los Santos provides a lavish and largely cohesive recreation of everyday life. Working-class Latino non-playable characters tend lawns in the rich area of Rockford Hills (Beverly Hills) and return home by bus in the evenings to their homes in East Los Santos (East LA), while the sun sets across the city, resetting game tasks and the in-game stock exchange. Random events and encounters with strangers are dynamic elements that add depth and unpredictability to the game. These events can occur spontaneously as you explore the game world, or they can be triggered by specific actions or locations.

Pixelated Promised Land

Intriguingly, a game known for car jacking and violent assault has become a popular treatise on one of the most celebrated national beliefs: the American Dream. Rooted in revolution and the overthrow of colonial powers, the American Dream has evolved into an amorphous but alluring myth celebrating individualism, freedom, opportunity, materialism, and personal success.

From Langston Hughes to Hunter S. Thompson, critics have long pointed out the limits and failings of the so-called American Dream, particularly its inaccessibility to minorities and the working classes. That critical media commentary now extends to games, with the Grand Theft Auto series offering valuable social commentary on the twenty-first-century version of the American Dream.

In narrative terms, character stories across the series highlight the futility of upward social mobility, or “uplift.” Consider the story of Niko Bellic in GTA IV, an Eastern European war veteran arriving in New York City hopeful of what a new nation can offer, but caught instead in a cycle of crime and violence. Initially drawn to Liberty City by his cousin Roman Bellic's exaggerated tales of wealth and luxury, Niko quickly discovers that Roman's life is far from the glamorous one he described, and becomes entangled in the city's criminal underworld. As Marc Ouellette notes, “[GTA provides] a relentless repudiation of the American Dream and its inherent contradictory ideologies”.

While Michael’s backstory explores white privilege, indulgences and frustrations surrounding living the Dream, Franklin’s story, as a young African American residing in a poverty-stricken part of Los Santos, underlines issues of economic and social exclusion. The gameplay experience aims to highlight the ironies and contradictions of modern American capitalism and the shortcomings of the American dream.

The Grand Theft Auto series is not unique in its critical assessment of the American Dream, with California, particularly Los Angeles, the focus. In his classic Beat novel The Dharma Bums (1958), Jack Kerouac described L.A. as “a regular hell” where “the air stank” and “the smog was heavy”. In the 1980s, writer Carolyn See surmised the appeal of Los Angeles as “It looks good, but that’s it”, and pronounced “the West Coast is the end of the road for the American Dream”.

The franchise plays to a long history of conceptualizing the West Coast as a realm of both bright futures and dark fortunes. Of interest here is how far Grand Theft Auto extends existing narratives and offers new interpretations through interactive design.

Death of a Salesman (by grenade launcher)

Collectively the game's mechanisms produce a distinctive form of digitally enhanced satirical play. Traditionally referring to the art of drama and live theatre, a satirical play is a performance marked by dark humor and ridicule, often targeting the government, corporations, or social institutions for their misdoings. Historic examples include Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Hamlet.

The term “satirical play” might be expanded to other forms of media that feature parody and ridicule. In the 1960s, Stanley Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove (1964) delivered tongue-in-cheek witticisms on American geopolitics and the Cold War. In recent decades, satire-heavy television programs such as South Park, Seinfeld, and Curb Your Enthusiasm have found commercial success and earned artistic acclaim.

Digitally rendered as a video game, satirical play takes on similar but arguably more expansive meanings. The “open stage” becomes the entire game world, the actors playable and non-playable game characters, and the dramatic narrative is delivered through a range of mutually enforcing mechanisms. The message is transmitted not just through character dialogue and thoughtful game world details but, uniquely, through player agency. In contrast to the satire of a Shakespearean stage play 'delivered' to an attentive audience, satire in a video game is revealed through direct action and personal experience.

Ad Nauseam

The mechanics of environmental immersion—of feeling part of a living, breathing simulation of Southern California—includes a range of highly accessible satirical content (or immersive satire), in the form of billboards, radio advertising, and websites as well as in-game social media and television commercials.

All told, GTA V contains approximately 550 billboards selling everything from fast food ("Slurry in a hurry!"), lawyers and realtors, credit and debt associations, coffee and chicken ("Going cheep!"), plastic surgery, and reality television (Rehab Island). Everything is “for sale” and eminently consumable.

The billboards underline a way of life based around themes of vapid consumerism, excess consumption, and mass gullibility. Advertising offers a window into what people buy, and is employed as a powerful device for storytelling, world building, and cultural commentary.

Over exaggerations and lies are common with billboard advertising. Fleeca Banks, for example, attracts customers by promising “Money for nothing, no problem.” Cluckin Bell (likely inspired by fast food chain Chick-fil-A) sells chicken “better than roadkill”, revealing both the poor quality but equally the mass acceptance of that poor quality.

Gun store Ammu-Nation warns freeway drivers, “take a break before you kill someone,” presenting Americans as a people on the edge of violence but then catering to and even encouraging such urges in pursuit of profit. "Slip and fall into the good life with the top employment law firm in San Andreas” boasts the website of law firm Hammerstein & Faust.

Tune in, tune out

Traveling between destinations, completing missions, and joyriding, the player spends considerable time sitting inside vehicles. The car radio always entertains during these periods and is one of my favorite features in the game. The in-game radio can tune to sixteen stations playing more than 441 tracks of licensed music, as well as two talk radio stations (“Weazel News, Confirming your prejudices!”).

The radio is largely unavoidable in-game and a wickedly effective satirical tool. The player, by their choice of station, has control over the messaging they wish to hear.

Blaine County Radio, for example, is Rockstar’s version of conservative talk radio. In the song “I Like Things Just the Way They Are,” frequently played on Blaine, the country singer Samantha Muldoon longs for a world of “old American values” where people “pray at the start of every football game” and “smoke in restaurants,” with “everything pure, just like in the South.” Muldoon targets the liberal political agenda, singing, “you lefties have just taken things too far.” Rockstar thus parodies conservative Americans longing for a time when, as Muldoon sings, “things were just great,” and the American Dream embodied Christian conservative values.

The radio also features over one hundred advertisements. Catchy jingles and hyped up narrators sell cars and alcohol rehabilitation to the masses. Mainstream U.S. brands are parodied. The commercial for Up-n-Atom Burger (In-N-Out Burger) has the taglines, “from a time when America didn’t worry about global warming, cholesterol or who can vote,” and “from when we were morally superior.” The burger chain has a retro, 1950s inspired diner style similar to Johnny Rockets restaurants.

Other radio adverts, such as the campaign for the fictitious Proposition 14, call for a return to the “golden age” of the Twenties and the return of Prohibition. In these examples, Rockstar presents the Dream as an expired concept out of touch with contemporary American needs and issues. You can practically hear the chants to "Make Los Santos Great Again!"

Excess and overconsumption is a common theme on the radio, reinforcing the popular idea of Americans as super-consumers. Windsor Real Estate advertises its services to the Los Santos rich with the line, “Look down on people, live the American Dream residing in a Mansion with an immigrant who hates you,” and frames home ownership as a status symbol.

Radio advertising also plays on popular anxieties. Strangely upbeat announcers warn their listeners of a fast-unfolding dystopia where the American Dream has no reach or relevance. They highlight social and environmental problems about to overwhelm Los Santos and the wider San Andreas community.

Taco Bomb (Taco Bell) promotes itself as a chain that has “fed students, poor people, and drunks since the 1970s” (the first restaurant actually opened in 1962). Proposition 45 calls for mandatory gun ownership and concealed carry for Americans so that they can protect themselves in an increasingly violent world. "Your lifestyle doesn't need to change just because you've maxed out your credit cards. Don't worry about your Interest rate! Consolidate!" proclaims an ad for Credit Card Consolidation Kings.

References on the radio of Los Santos falling apart are easily confirmed by the player looking out their windshield. Evidence of the failed experiment of the American Dream is hard to miss across areas of Los Santos. In-game locations such as Strawberry and Rancho in South Los Santos depict the urban blight of real-life Crenshaw, Watts, and Florence.

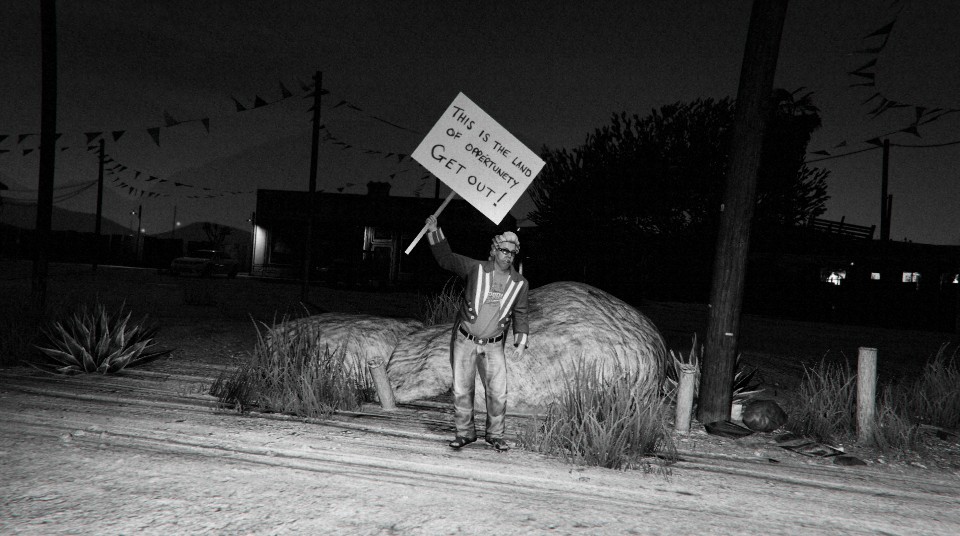

Artist Morten Rockford Ravn has documented the depravity of Los Santos in a series of digital street photographs, taken in-game, that highlight the social wasteland. Inspired by Hunter S. Thompson’s “gonzo journalism,” Ravn’s pictures depict homeless men and their carrier bags on Del Perro Beach, abandoned gas stations, and cutthroat gangs on street corners. The pictures collectively impart a ghostly image of depravity and decay, and of American society some distance from the realization of the American Dream, digital or otherwise.

The billboards and jingles of Grand Theft Auto V impart a dual message to the player. With their overt, brazen parody, they remind the player that GTA exists as an outlandish and hyperreal representation of America. Secondly, Rockstar’s adverts reveal disturbing facts about real-life society.

In-game company slogans offer more truth than their real-life counterparts. When FlyUS air fleet uses the slogan “Sit back, relax, and shut up,” that message resonates with anyone who has ever flown Spirit or Frontier Airlines. The satirical point of billboards and jingles in Grand Theft Auto is frequently to highlight how the American service economy may claim to offer its customers the American Dream, but how that lifestyle remains elusive.

Freud and firepower

As in The Sopranos (1999), therapy sessions offer a rare glimpse into a character's psyche, family dynamics, and the complexities of the criminal underworld. A frustrated and angry Michael reflects to his psychiatrist Dr. Friedlander how the “opportunities” and “achievements” of crime have allowed him to live a rich and quiet life with his family in posh Rockford Hills. Despite his material success, Michael is struck how unfulfilled he actually feels. The luxury lifestyle seems innately hollow and aimless, with most of his free time spent watching daytime television coupled with daytime drinking. As he laments to his shrink, “I’m rich, I’m miserable.”

Similar to characters in a book, the narratives of Michael, Franklin, and Trevor serve as the “storyline” for the player. While Franklin, an African American caught in poverty, is presented as someone who is, by race and status, striving for but consistently denied the Dream, and Trevor, as psychopath and killer, seems to outwardly reject any social norms or ideals, the character of Michael is most revealing precisely because he is ostensibly a Los Santos success story.

Michael has achieved success through various nefarious schemes, and his character clearly identifies with the twenty-first-century goals of real estate, comfort, and riches. His property in the Rockford Hills neighborhood is an archetypal Hollywood mansion, with motorized gated access, a movie room, and swimming pool. He also owns a luxury yacht and has an attractive wife and two kids.

Inwardly, Michael feels imposter syndrome living in Rockford Hills, with the quiet existence a poor fit for his rebellious nature. As Michael points out to Amanda in a family therapy session, “we’re trailer trash, you and me.” This sense of “roleplaying” the American Dream is further underscored by Dr. Friedlander’s commentary when he probes Michael on his true feelings and motivations.

Michael’s nuclear family also seems highly dysfunctional and disconnected. He moans to Dr. Friedlander about his lazy and privileged son Jimmy, who has all the advantages in the world but no compulsion to work. His wife Amanda cheats behind his back with her tennis coach and bemoans in a group session Michael’s endless “sarcasm.” While outwardly a strong and rich man “living the dream”, the noir side is revealed as the game progresses.

In a meta twist, Rockstar has Michael frequently question if someone is mysteriously controlling him. Dr. Friedlander also consistently asks Michael to stop “acting out.” Such mechanisms help the player listen to Michael’s inner voices but also encourage reflection on their own experiences of American life. Satirical play involves "being" Michael but also being a player that appreciates and develops their own critical and ironic perspective.

Michael’s growing disillusionment with the classical American Dream also underlines its greater insufficiency. For Michael, the draws of returning to crime outweigh the rewards offered by continuing to “live the Dream.” In his third session with Dr. Friedlander, while accepting that falling back into a life of crime signified a “bad relapse,” Michael professes how it “felt good,” and far more exciting than his usual banal existence. Crime seems to be a part of Michael’s individual calling, or even human nature. In their final session together, he confides to Dr. Friedlander that, “I want to be a good dad, love my family, live the dream,” but that the siren call of crime always conquers those “sunshine” daydreams.

For the player regularly occupying Michael’s shoes, as well as attending his therapy sessions, crime also seems more compelling than abiding by the law. GTA is infamous for car chases and killing, not sitting on the sofa watching Rehab Island on TV for a reason. This conflict between what a game's narrative (story, themes, and characters) conveys and the actual gameplay mechanics is called ludonarrative dissonance.

The term was coined by game designer Clint Hocking in 2007 to describe how he felt playing Bioshock (2007). Bioshock presents a story about free will and challenging a tyrannical system, but the core gameplay loop requires players to make choices that contradict this theme, such as harvesting Little Sisters for upgrades.

Move fast and blow things up

One early mission involves a calculated attack on social media giant LifeInvader, a thinly veiled parody of Facebook. LifeInvader is Los Santos' leading social media network, with most game-characters using its mobile app and having their own online profiles. The company aggressively markets its new products with slogans such as “Peek, Pry, Populate” and “Create Friends today.” Other in-game companies advertise on LifeInvader and encourage the player to visit their corporate profiles (“Stalk us on LifeInvader!”). The encouragement to “stalk” spoofs the Facebook “like” button and our culture of obsessively following others on social media, which has only grown worse since the games introduction.

Michael’s associate Lester Crest nurtures a hatred for LifeInvader and tasks the player with sabotaging the company. Lester provides Michael with a tiny package to be attached to a new LifeInvader prototype sequestered at the corporation’s headquarters. Undercover as a pretend employee, Michael gains the trust of co-workers at the LifeInvader office before targeting the prototype.

The company's office is a parody-rich mockery of the California technology industry. Posters on the wall motivate employees to "live tomorrow," while recreational spaces include a "yoga zone," a "sweat lodge," and an "imagineering" room (a likely reference to Disney Imagineering). Michael is told to "chill out" on a beanbag chair while waiting for his meeting to start.

Oblivious to Lester's ultimate aims or the true contents of the package, Michael calls the CEO of the company Jay Norris as he presents the device at a Keynote event on live television. The call triggers the sabotaged prototype to explode and assassinate Norris, tanking the company's stock.

The LifeInvader mission critiques life in Silicon Valley and mocks the values espoused by Big Tech. Rockstar challenges the culture of tech-companies where employees are encouraged to embrace their creativity, worship new age slogans, and sit in beanbags instead of chairs. Norris, the CEO, is presented as a charismatic Steve Jobs-like character who emphatically imparts his ruthless ambition as well as his techno-optimism. He promotes his youthful, next-generation workforce (who average "14.4 years in age") and talks of "weapons grade domination” of the technology sector thanks to his new mobile devices.

Surprisingly, given its own role in the video game sector, Rockstar gets the player to target a technology giant. By assisting Lester, Michael (and the player) become unwitting accomplices to murder. By targeting LifeInvader, they also take aim at the millennial generation’s America rooted in technology, futurism, and social media likes.

The Satire of Play

Despite the compelling story mode, the real reason for GTA V's enduring success is its multiplayer component, GTA Online. Though it was considered a flop when first released, Rockstar has steadily upgraded the online mode into a highly polished product. Regular updates offer players new missions, vehicles, and the chance to run nightclubs where they can launder their ill-gotten gains. When alien body suits were introduced as a wearable item, large groups of players dressed up as green and purple aliens and spontaneously engaged in combat. The Alien Gang war, as it came to be known, became a major online event, with players creating dedicated subreddits, Discord servers, and TikTok accounts to document their experiences and coordinate attacks. Rockstar has thus provided the tools for players to create their own virtual culture and history.

Some updates allowed players to build communities online, to form biker gangs or hire each other in complex mob hierarchies. GTA Online slowly evolved from an absurdist crime simulator into a virtual life where people simply went to hang out with friends and drive cars they could never afford in the real world.

Rockstar has thus provided the tools for players to create their own virtual culture and history.

One thriving community has dedicated role-play servers, where players are assigned everyday jobs and perform their roles in character, be they postal workers or ambulance drivers. Some work real-time eight-hour shifts as virtual cops, arresting drug dealers and handing out fines for traffic violations. Role players stream their gameplay on Twitch, which viewers enjoy in their thousands.

That the player has an active role in attaining their own digital “American Dream” highlights the active participation necessitated in all video games. Unlike other entertainment media, storylines and outcomes depend on input from the audience. The "open world” format of the game, with its powerful physics engine and play possibilities, invites the player to explore and experiment.

Rockstar also made the wise choice early on to allow players to tinker with the game’s software. It introduced an editor mode which lets players direct the world’s time, weather and denizens to create films with video game casts (known as “machinima”), which range from nature documentaries to shot-for-shot James Bond recreations. Those who want to dive deeper still can join a community of “modders” who edit the software to update graphics or add features such as superheroes or an LGBT pride parade. The best mods are the strangest: hack the game to run around the city not as a human but as a peaceful deer, or harness the power of magnificently surreal guns that shoot cars or sharks.

Crime pays

GTA V’s financial returns have been legendary. In 2013 it broke industry records as the fastest entertainment product to reach $1 billion in revenue (making $800 million on day one and grossing $1 billion in 3 days). Subsequent releases and the growing success of GTA Online greatly expanded the revenue stream. Take-Two’s CEO noted that GTA Online’s recurring player spending has been a key revenue driver, “consistently generating over $500 million annually” in the last few years. Fiscal year 2021 saw GTA Online earnings of roughly $985 million from microtransactions – illustrating how online content has sustained revenue long after initial release.

Physical & digital revenue distribution per year

As of March 2025, GTA V was reported to have shipped over 215 million copies worldwide across all platforms – making it the second best-selling video game of all time (behind Minecraft). Notably, PlayStation consoles account for the largest portion of units. By 2020 around 20 million copies had been sold for the PS4 alone. Demand has also been strong globally, with ~30% of sales from North America and ~50% from Europe, evidence of the game's broad international appeal.

Console capitalism

With Grand Theft Auto VI on the horizon, industry expectations are sky-high. Take-Two Interactive is projecting “record” financial results in the release year, with net bookings forecast to exceed $8 billion when GTA VI launches. This would roughly double Take-Two’s typical annual revenue – a clear sign that the game is expected to be an unprecedented cash cow.

Market research firm DFC Intelligence forecasts the game will sell tens of millions right out of the gate – possibly around 40 million copies in its first 12 months, generating about $3 billion in first-year sales . Remarkably, over $1 billion in revenue could come before release day, as analysts project pre-order sales alone topping $1B (millions of fans putting down deposits).

Several financial analysts have stated GTA VI is “expected to be an instant hit with billions of dollars in sales each year” once it releases. In fact, franchise records set by GTA V are likely to be surpassed. DFC predicts GTA VI will reach 100 million units sold within ~5 years of launch – a much faster pace than GTA V, which took about 11 years to hit 200 million. Some forecasts even suggest GTA VI might clear 50 million units in its launch quarter if initial supply meets demand, given the expanded console install base during the COVID-19 pandemic and pent-up fan enthusiasm.

To capitalize on the hype, Rockstar is reportedly considering a premium pricing strategy: there is speculation that GTA VI could debut at a $90–$100 price point for the base game, breaking the industry’s $60-$70 norm. Such a price would boost early revenue – and many expect consumers would still rush to buy the game even at $100, due to the immense anticipation.

Total copies sold within first 12 months of release

The End of the American Dream

With the Grand Theft Auto series, Rockstar Games has extended satirical theater in new directions and imbued it with new levels of interactivity. Satire transforms from a passive form of comedy and commentary not just watched and enjoyed, but co-authored and co-developed through play. This is a significant progression and highlights how games can further our own sense of humor and creativity.

Outwardly, GTA V operates on the premise that the American Dream has perhaps always been little more than an empty “myth” for most Americans. GTA V thrives in its depiction of the American Dream gone wrong: the sarcasm, the violence, and the “noir” is what makes the series so appealing. For centuries the American Dream has inspired celebration, dedication, and broad-based belief. Today, by its global reach and sales figures, Grand Theft Auto preaches disillusionment on a mass scale. The game is, by design, a timely experience, marked by moments of intense violence, confrontation, and nihilism. GTA V is a good example of how video games reflect the contemporary American condition and can be used to explore some of the problems of U.S. society and politics.

The continued success of GTA V points to how game development is evolving. Players no longer buy titles for a single experience, to be completed once and discarded. Now games are built as platforms that are updated over time, from which developers continue to profit from microtransactions. This business model divides the opinions of gamers, but it allows a single game to stay relevant over generations of consoles because there’s always something new to do. The fictional state of San Andreas has become a playground and home for gamers like no other. While they await news of GTA VI, it is easier to return to these familiar haunts than try something new. They have grown up with this game, and it has grown with them, too.