Post

Nexus: A Brief History of Information Networks

We're all cooked

Author Yuval Noah Harari brilliantly captures the modern age in Nexus, his latest book. Drawing on a fascinating range of historical examples, from the Stone Age and the Bible to early European witch-hunts, Stalinism, Nazism and the resurgence of populism today, Harari gives us a powerful framework through which to understand the complex relationship between information and truth, bureaucracy and mythology, wisdom and power. He presents the various existential crises humanity faces, like global warming and fears of non-human intelligence, as big information-related challenges.

Few can elucidate the moral and technological dilemmas facing humanity today quite like Yuval can. As clear as his writing is, I grew increasingly anxious the closer I got to the end of Nexus. After outlining the historical examples of information misunderstanding and abuse, Harari presents dire potential consequences of information created by Artificial Intelligence: “The rise of intelligent machines that can make decisions and create new ideas means that for the first time in history power is shifting away from humans and toward something else.” He worries that machines will become more intelligent than humans, but without feelings. “Since the current information revolution is more momentous than any previous information revolution, it is likely to create unprecedented realities on an unprecedented scale.”

He describes the "naive view" of information, which assumes that more information is always better and likely to lead to the truth. Yuval excoriates this position, reminding us that the hyperconnected internet did not end totalitarianism, and racism cannot be fact-checked away. But he also warns against a “populist view” that objective truth does not exist and that information should be wielded as a weapon.

"Nexus" is a story in two parts. The first half examines the significant consequences of misused information throughout history. This is familiar territory for the historian and best selling author, who delivers these stories with clarity and confidence. The second half of the book offers parables for understanding the upheaval AI ("alien intelligence", Yuval convincingly argues) will unleash.

The historical examples used to demonstrate the misunderstanding and misuse of information are compelling because Harari knows so much about historical events throughout the world. His explanation of how the Bible’s New Testament was compiled reveals how the assembly of information is often a debate about what matters and what doesn’t, based only on the included information. Different branches of Christianity disagree about what should be considered sacred texts. “We do not know the precise reasons why specific texts were endorsed or rejected by different churches, church councils, and church fathers. But the consequences were far-reaching.”

Consider the example I Timothy, a letter in the New Testament, which calls for the full submission of women, and rejection of the Acts of Paul and Thecla, which gave women leadership roles, “describing how Thecla not only performed numerous miracles but also baptized herself.” Some consider I Timothy a forgery despite its place in the New Testament. If Thecia had been included in the Bible, world history, at least in the Western world, might have experienced a major change in attitudes toward the role of women. But one piece of information won and another lost, with significant results.

Observations

Who is Cher Ami?

A carrier pigeon named Cher Ami delivered a crucial message which saved hundreds of soldiers from certain death despite not understanding the contents of the message. This demonstrates how information can take various forms (like a pigeon carrying a note) and can have real-world consequences independent of the sender's or recipient's understanding of its significance. Thinking about information taking the form of letters sent by carrier pigeon makes it easier to conceptualize how data is shared in a computer network.

What are stories and lists?

Stories inspire and create a sense of identity and purpose, while lists provide the essential data and organization needed for bureaucratic functions, like tax collection, and maintaining complex societal structures, like empires. Human bureaucracies struggle to retrieve information from vast archives of written documents, requiring organized systems to manage increasing amounts of data. So far in history (e.g. Stalinism, Nazism) it has been impossible to process all this information. Advancements in information technology and the way AI works means that processing information like this is actually a huge benefit, not a downside. Indeed, a centralized information system will be precisely the ideal sort of data vacuuming environment for an AI to flourish in.

🎵 Is music information?

Music connects people and synchronizes their emotions and movements, creating collective experiences without needing to represent reality. For instance, marching soldiers, conga line dancers, and sports fans all find unity and connection through shared musical experiences. They are new intersubjective realities, meaning between two subjects (or nodes, in an information network).

What are intersubjective realities?

Intersubjective realities like nations, laws, and currencies exist through collective belief and shared narratives. This allows for large-scale organization among humans. Each improvement in information technology has connected a greater number of people than the previous generation.

What is the Bible, in the context of an information network?

Yuval points out that all religions (Christianity, Islam, Judaism, etc.) have tried to codify the words of a higher power in holy text. The Bible was curated by a counsel of the church elite and widely distributed by the Roman Catholic church (while simultaneously suppressing alternative religious scripture). While the Bible may contain inaccuracies about human history and nature, its true power lies in its ability to connect billions of people, creating religious and social networks that endure over time, highlighting the primary role of information as a connector.

We’re living through the most profound information revolution in human history, but we can’t understand it unless we understand what has come before. History, after all, isn’t the study of the past–it is the study of change. It teaches us what remains the same, what changes, and how things change. History is not deterministic, however, and NEXUS doesn’t argue that understanding the past enables us to predict the future. My goal is to show that by making informed choices, we can still prevent the worst outcomes. Because if we can’t change the future, then why waste time discussing it?

— Yuval Noah Harari

How do self-correcting mechanisms operate in different institutions?

Self-correcting mechanisms are essential for institutions to survive over time. In scientific institutions, these mechanisms may involve practices such as peer review and public dissemination of new information, where scholars actively seek to find and rectify mistakes. Conversely, religious institutions do not possess strong self-correcting mechanisms, often causing them to obscure their errors instead of embracing correction.

But even scientists have a tendency to resist change, with resistance to new findings that challenge common understandings at the time. The contradiction of Newton’s laws by quantum theory is one example. Still, Yuval notes that new paradigms usually emerge: “The self-correcting mechanism embraces fallibility.”

Thus the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is able to update and amend itself to remove homosexuality as a diagnosis in just 22 years, but the Catholic church is unable to update it's Holy text and must shift blame for any "misinterpretation" of their infallible text.

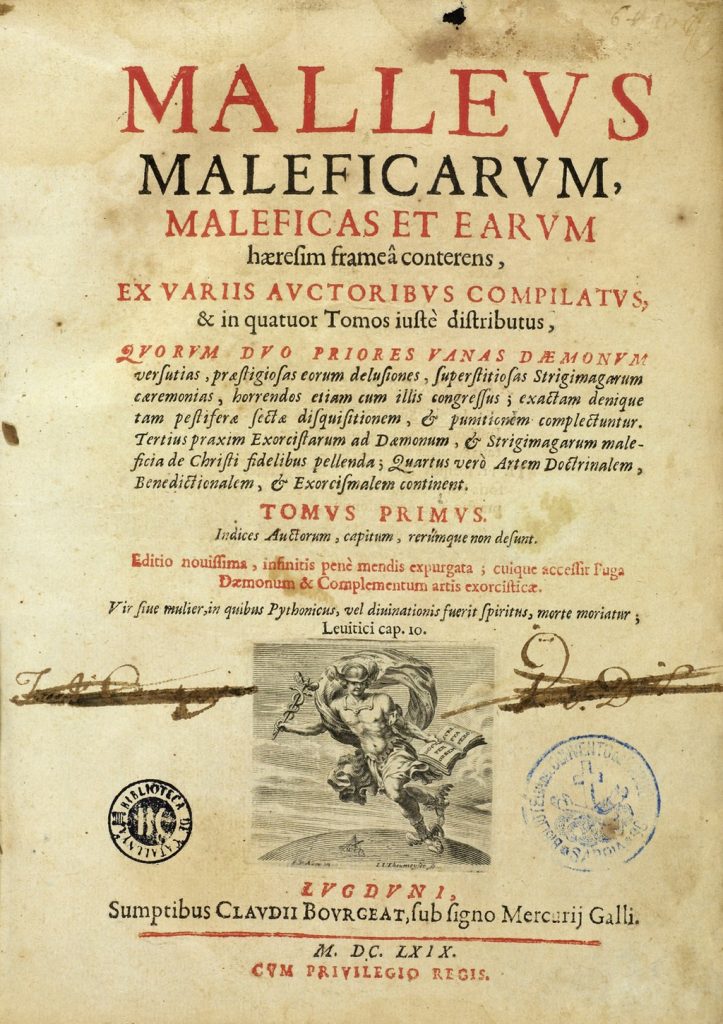

How do witch hunts illustrate the complexities of information networks?

Heinrich Kramer's Malleus Maleficarum (Hammer of Witches), published in 1487, led to mass panic across Europe as people feared witches in their communities and even in their own families. The power of the printed word allowed the sensationalist stories and lurid details to spread far and wide.

The witch hunts demonstrate that the spread of sensational and false information can lead to mass hysteria and tragic outcomes. They highlight the power of narrative and the dangers of unchecked information, showing how belief systems can be influenced by social dynamics rather than objective truths.

As literature accumulate about witches, from lists of alleged witches to obtained confessions and "documentation" on witch activities, it becomes hard for humans to realize that the entire silo of knowledge about the subject contains not a single grain of objective truth.

How does the flow of information differ between democracies and dictatorships?

In democracies, information flows in a decentralized manner in which multiple independent channels allow for diverse communication and decision-making. This creates an ongoing conversation among various nodes such as citizens, media, and institutions. In contrast, dictatorships feature a centralized network where information flows to a single authority, limiting transparency and accountability. This central hub dictates everything, stifling dissent and debate.

Technology significantly impacts the structure and function of political systems. It can enhance democracy by facilitating communication and information between citizens, fostering participation and engagement such as an app developed to enhance situational awareness in the event of an earthquake. Conversely, technology can empower totalitarian regimes by enabling centralized control and surveillance, allowing these systems to monitor and repress dissent effectively.

Modern information technology can amplify extreme voices, spread misinformation, and polarize public opinion, posing risks to democratic discourse. The ease of dissemination can lead to manipulation of information and erosion of trust in democratic institutions, challenging how societies engage in civil dialogue.

How has the evolution of computers changed the power dynamics in society?

The rise of computers has transferred power from humans to machines, as computers are capable of making autonomous decisions and generating new ideas. Unlike previous tools such as printing presses and radios, computers function as active agents that can influence social and cultural dynamics, leading to unprecedented changes in how society operates.

If computers can compose and interpret narratives, they may manipulate human beliefs and opinions, impacting political and social structures. This could lead to a future where human culture and society are heavily influenced—or even controlled—by nonhuman intelligences crafting convincing narratives and fostering intimate relationships with users.

In a lot of ways, the IT department of every company is going to be the HR department of AI agents in the future

— Jensen Huang, 2025 Nvidia keynote 🤮

How has surveillance evolved from ancient times to today?

Surveillance has transformed from manual human monitoring by families and communities in ancient times to complex bureaucratic systems aimed at controlling populations through data collection and analysis. Initially, humans were watched by peers, nosy neighbors, and authority figures like rulers and priests. Technology today allows for near universal surveillance, where computers and AI can continuously track our activities, behaviors, emotions and even thoughts in real-time.

What role does fear play in totalitarian surveillance regimes?

Fear is a crucial weapon in totalitarian regimes, as it creates a populace that is self-regulating. Even though a regime cannot monitor every action by every person constantly, the mere possibility of surveillance leads citizens to self-censor and adhere to oppressive norms from paranoia. The dread of the Gulag and the Soviet secret police is enough to keep people in line. Digital agents, however, have no fear and won't be intimidated. They also have a nasty habit of calling out the doublespeak so common in our politics.

How can systems of accountability be established for intelligent algorithms?

Depressingly this feels like the weakest part of the book to me. Systems of accountability for intelligent algorithms could be established by creating regulatory frameworks that include ethics panels, regular technology audits, and mechanisms for public input and scrutiny. This multifaceted approach would help ensure that these systems operate in alignment with human values.

Harari outlines several principles for the survival of democracy including benevolence (technology should serve citizen's interests), decentralization (information should not be controlled by a single entity), mutuality (both citizens and governments should be monitored), and the importance of allowing for change and rest. These principles aim to maintain democratic integrity and accountability in an increasingly automated world.

While there are glimmers of hope, it seems far more likely that power will accrue to a few aggregator tech companies and governments that can afford the tremendous energy costs demanded by the best AIs.

Yuval Noah Harari

Professor Yuval Noah Harari is a historian, philosopher, and the global bestselling author of Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow, 21 Lessons for the 21st Century, the graphic adaptation series Sapiens: A Graphic History, and Unstoppable Us, his first series of books for children.

His books have sold over 45 million copies in 65 languages, with Sapiens alone selling 25 million copies since it was first published in 2013. A New York Times and Sunday Times #1 bestseller, Yuval Noah Harari is widely considered to be a pretty smart guy.