Out there

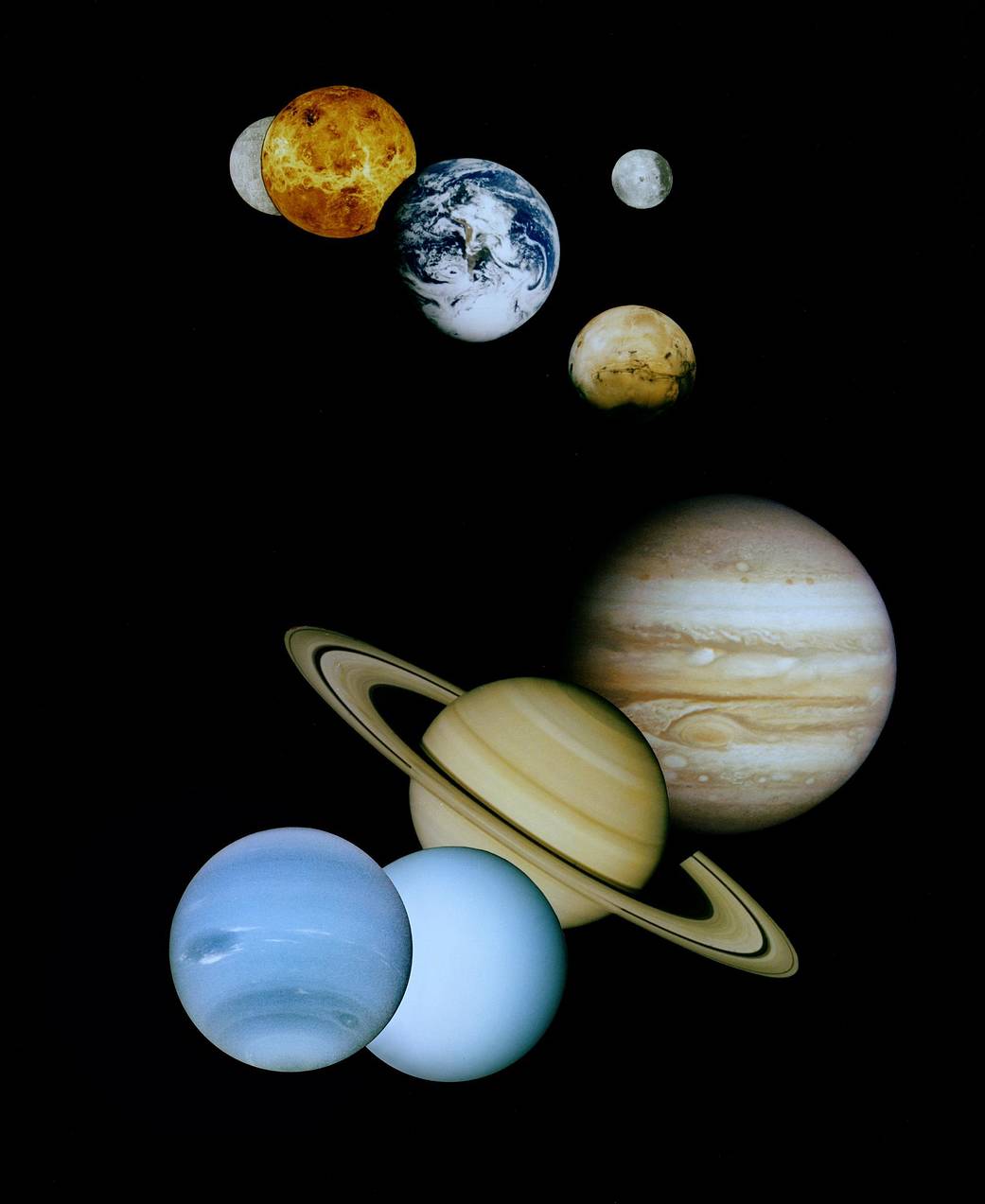

Planets of our Solar System

Our solar system consists of the Sun and many smaller objects: the planets, their moons and rings, and miscellaneous “debris” like asteroids, comets, and dust. Centuries of observation and decades of spacecraft exploration have revealed that most of these objects formed together with the Sun about 4.5 billion years ago. They represent clumps of material that condensed from an enormous cloud of gas and dust. The central part of this cloud became our Sun, and a small fraction of the material in the outer parts eventually formed the other objects.

Our understanding of our place in the cosmos is constantly evolving. In addition to gathering information with powerful new telescopes, humans have sent spacecraft directly to many members of the planetary system. With evocative names such as Voyager, Pioneer, Curiosity, and Pathfinder, our robot explorers have flown past, orbited, or landed on every planet, returning images and data that have dazzled both astronomers and the public. In the process, we have also investigated two dwarf planets, hundreds of fascinating moons, four ring systems, a dozen asteroids, and several comets.

Our probes have penetrated the atmosphere of Jupiter and landed on the surfaces of Venus, Mars, our Moon, Saturn’s moon Titan, the asteroids Eros and Itokawa, and the Comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko (usually referred to as 67P). Humans have set foot on the Moon and returned samples of its surface soil for laboratory analysis. We have even discovered other places in our solar system that might be able to support some kind of life.

The Sun

The Sun

At the center of our solar system is a star called the Sun. The Sun, a star that is brighter than about 80% of the stars in the Galaxy, is by far the most massive member of the solar system, as shown in the table below. It is an enormous ball about 1.4 million kilometers in diameter, with surface layers of incandescent gas and an interior temperature of millions of degrees. In addition, the Sun contains more than 99 percent of all the material in the solar system.

It has a core temperature of more than 28M° F (15,600,000° C). The sun constantly changes the hydrogen in its core into helium. This process gives out huge amounts of radiation, or energy. Living things on Earth depend on this energy in the form of light and heat.

| Mass of Members of the Solar System | |

|---|---|

| Object | Percentage of Total Mass |

| Sun | 99.80% |

| Jupiter | 0.10% |

| Comets | 0.0005–0.03% (estimate) |

| All other planets and dwarf planets | 0.04% |

| Moons and rings | 0.00005% |

| Asteroids | 0.000002% (estimate) |

| Cosmic dust | 0.0000001% (estimate) |

This table also shows that most mass in our solar system is actually concentrated in the largest planet, Jupiter, which is more massive than all the rest of the planets combined. Astronomers were able to determine the masses of the planets centuries ago using Kepler’s laws of planetary motion and Newton’s law of gravity to measure the planets’ gravitational effects on one another or their moons. Today, we make even more precise measurements of planetary masses by tracking the gravitational effects on the motion of spacecraft that pass near them.

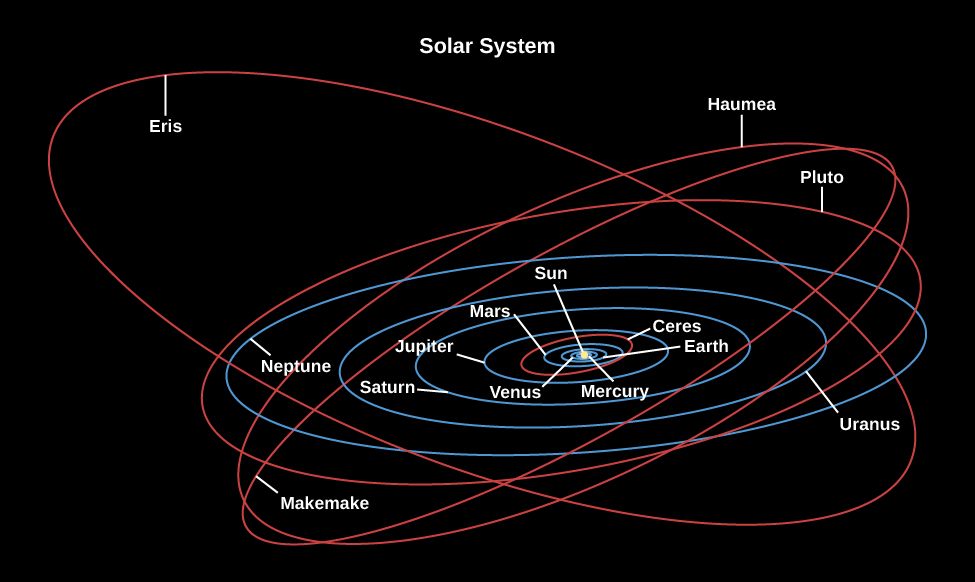

Besides Earth, five other planets were known to the ancients—Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn—and two were discovered after the invention of the telescope in the early 17th century: Uranus and Neptune. Besides these planets, we have also been discovering smaller worlds beyond Neptune that are called trans-Neptunian objects or TNOs. Pluto was the first one of these to be found, in 1930, but others have been discovered during the twenty-first century. One TNO, Eris, is about the same size as Pluto and has at least one moon (Pluto has five known moons). The largest TNOs are also classed as dwarf planets, as is the largest asteroid, Ceres. To date, more than 1,750 TNOs have been discovered!

Orbits of the Planets

The eight planets all revolve, or spin, in the same direction around the Sun. They orbit in approximately the same plane, like cars traveling on concentric tracks on a giant, flat racecourse. Each planet stays in its own “traffic lane,” following a nearly circular orbit about the Sun and obeying the orbital “traffic” laws discovered by Galileo, Kepler, and Newton.

Each of the planets and dwarf planets also rotates (spins) about an axis running through it, and in most cases the direction of rotation is the same as the direction of revolution about the Sun. The exceptions are Venus, which rotates backward very slowly (that is, in a retrograde direction), and Uranus and Pluto, which also have strange rotations, each spinning about an axis tipped nearly on its side. The spin orientations of Eris, Haumea, and Makemake are currently unknown.

The four planets closest to the Sun (Mercury through Mars) are called the inner or terrestrial planets. The Moon is often included as a part of this group, bringing the total of terrestrial objects to five. The terrestrial planets are relatively small worlds, composed primarily of rock and metal. All of them have solid surfaces that bear the records of their geological history in the forms of craters, mountains, and volcanoes.

Mercury

Mercury

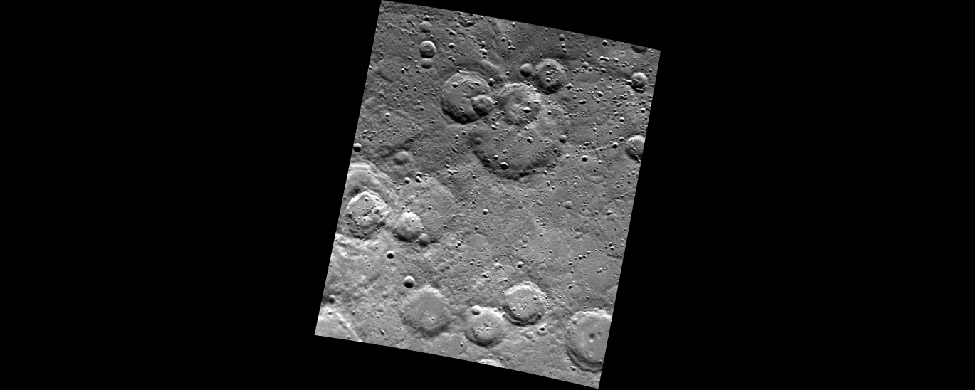

Mercury is the planet closest to the Sun. It has the shortest revolution time about the Sun (88 Earth days) and the highest average orbital speed (48 kilometers per second). Mercury is aptly named after the fleet-footed Roman messenger god. Because Mercury remains close to the Sun, it can be difficult to see in the sky. As you might expect, this planet is best examined when its eccentric orbit takes it as far away from the Sun as possible.

Mercury’s average distance from the Sun is 58 million kilometers, or 0.39 AU (astronomical unit). However, because its orbit has the high eccentricity of 0.206, Mercury’s actual distance from the Sun varies from 46 million kilometers at perihelion to 70 million kilometers at aphelion.

Mercury, being close to the Sun, is very hot on its daylight side. But because it has no significant atmosphere, it gets surprisingly cold during the long nights. The temperature on the surface rises to 700 Kelvin (430 °C) at noontime. After sunset the temperature plummets, reaching 100 K (–170 °C) just before dawn. (It is even colder in craters near the poles that receive no sunlight at all.) The temperature range of 600 K on Mercury is the greatest among the other planets.

The pockmarked face of Mercury is more typical of the inner planets than the watery surface of Earth. This black-and-white image, taken by the Mariner 10 spacecraft, shows a region more than 400 kilometers wide on the surface of Mercury.

Venus

Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun and is known for its thick, toxic atmosphere and extreme surface temperatures. It's often called Earth's "sister planet" because of their similar size and composition.

Venus appears very bright in the night sky, and even a small telescope reveals that it goes through phases like the Moon. Galileo discovered that Venus displays a full range of phases, and he used this as an argument to show that Venus must circle the Sun and not Earth. The planet’s actual surface is not visible because it is shrouded by dense clouds that reflect about 70% of the sunlight that falls on them.

Most of our information on the geology of Venus is derived from the US Magellan spacecraft, which mapped Venus with a powerful imaging radar. Magellan produced images with a resolution of 100 meters, much better than that of previous missions, yielding our first detailed look at the surface of our sister planet.

The Magellan spacecraft returned returned 1,200 gigabits of data, far exceeding the 900 gigabits of data from all NASA planetary missions combined at the time. Each 100 minutes of data transmission from the spacecraft provided enough information, if translated into characters, to fill two 30-volume encyclopedias.

Earth

Earth

The Earth is a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena. Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors so that in glory and triumph they could become the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot.

Carl Sagan

Earth is a medium-size planet with a diameter of about 12,760 kilometers. As one of the terrestrial planets, Earth is composed primarily of heavy elements like iron, silicon, and oxygen— very different than the composition of the Sun and stars, which are made of the lighter elements hydrogen and helium. Earth’s orbit is nearly circular, and you've probably noticed its warm enough to support liquid water on the surface. Earth is the only planet in our solar system that is neither too hot nor too cold, but “just right” for the development of life as we know it.

Look inside yourself

The interior of a planet— even our own Earth— is difficult to study, and its composition and structure must be determined indirectly. Our only direct experience is with the outermost skin of Earth’s crust, a layer only a few kilometers deep. It's humbling to remember that, in many ways, we know less about the planet 5 kilometers beneath our feet than we do about the surfaces of Venus and Mars.

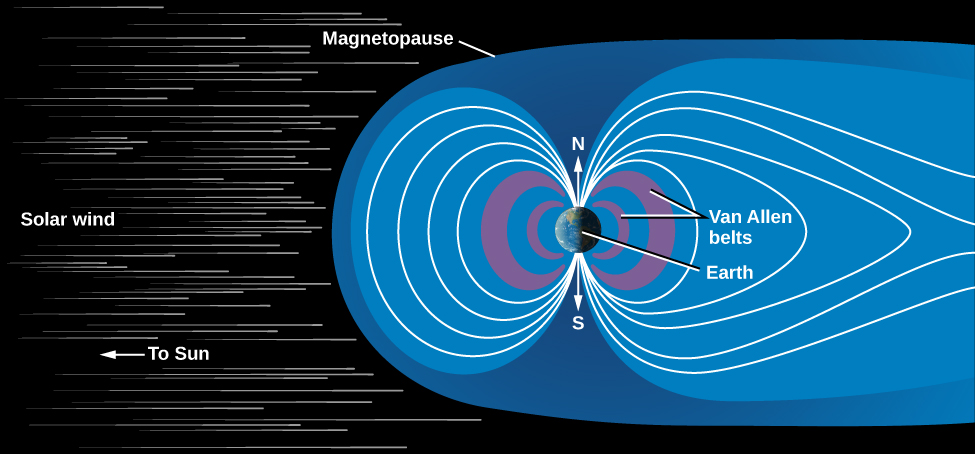

Magnetic field and magnetosphere

Our planet behaves in some ways as if a giant bar magnet were inside it, aligned approximately with the Earth's poles. This magnetic field is generated by moving material in Earth’s core. As the liquid metal inside Earth churns, it creates a circulating electric current. When many charged particles are moving together like this— either in the laboratory or on the scale of an entire planet— they produce a magnetic field.

Earth’s magnetic field extends into our atmosphere and surrounding space. When a charged particle encounters a magnetic field in space, it becomes trapped in the magnetic zone. Above Earth’s atmosphere, our field is able to trap small quantities of electrons and other atomic particles. This region, called the magnetosphere, is defined as the zone within which Earth’s magnetic field is stronger than the faint magnetic field from the Sun.

A cross-sectional view of our magnetosphere (or zone of magnetic influence), as revealed by numerous spacecraft missions. Note how the wind of charged particles from the Sun “blows” the magnetic field outward like a wind sock.

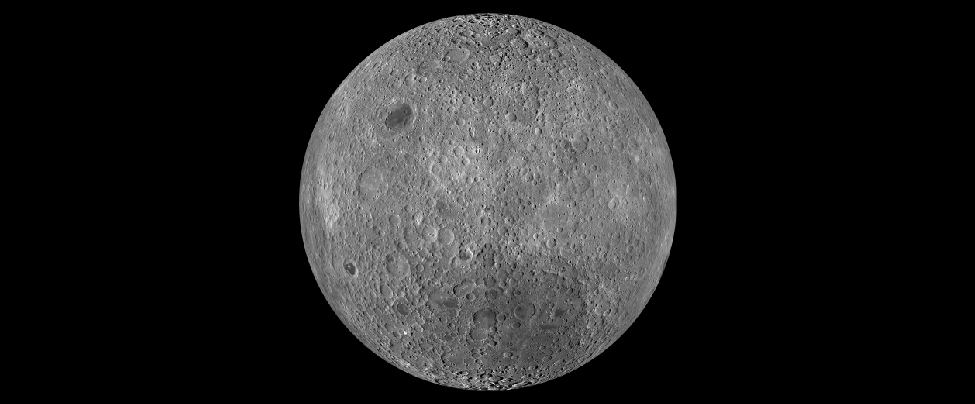

Our cratered Moon

This composite image of the Moon’s surface was made from many smaller images taken between November 2009 and February 2011 by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) and shows craters of many different sizes.

One of the nice perks of living on Earth at the present time is that the two most prominent astronomical objects, the Sun and the Moon, have nearly the same apparent size in the sky. Although the Sun is about 400 times larger in diameter than the Moon, it is also about 400 times farther away, so both the Sun and the Moon have the same angular size— about 1/2°. As a result, the Moon, as seen from Earth, can appear to cover the Sun, producing one of the most incredible events in nature.

Every solid object in the solar system casts a shadow by blocking the light of the Sun from a region behind it. This shadow in space becomes apparent whenever another object moves into it. In general, an eclipse occurs whenever any part of either Earth or the Moon enters the shadow of the other. When the Moon’s shadow strikes Earth, people within that shadow see the Sun at least partially covered by the Moon; that is, they witness a solar eclipse. When the Moon passes into the shadow of Earth, people on the night side of Earth see the Moon darken in what is called a lunar eclipse.

Mars

Mars

Mars, the fourth planet from the Sun, is often called the "Red Planet" due to its reddish appearance. It boasts the largest volcano and canyon in the solar system.

Mars has been frequently investigated by spacecraft. More than 50 spacecraft have been launched towards Mars, but only about half were totally successful. The first visitor was the US Mariner 4, which flew past Mars in 1965 and transmitted 22 photos to Earth. These pictures showed an apparently bleak planet with abundant impact craters. Newspaper headlines sadly declared that Mars was a “dead planet.”

In 1971, NASA’s Mariner 9 became the first spacecraft to orbit another planet, mapping the entire surface of Mars at a resolution of about 1 kilometer and discovering a great variety of geological features, including volcanoes, huge canyons, intricate layers on the polar caps, and channels that appeared to have been cut by running water. Geologically, Mars didn’t seem so dead after all!

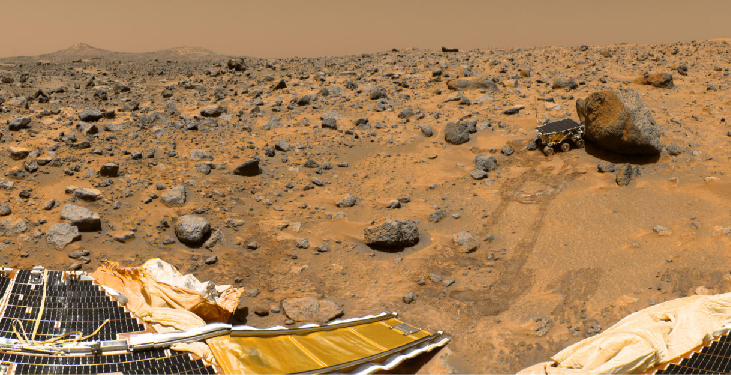

Surface view from Mars Pathfinder

The scene from the US Pathfinder lander shows a windswept plain, sculpted long ago when water flowed out of the martian highlands and into the depression where the spacecraft landed. In this photo, you can see the ramp from the lander and the path the rover took to the larger rock that the mission team nicknamed “Yogi.”

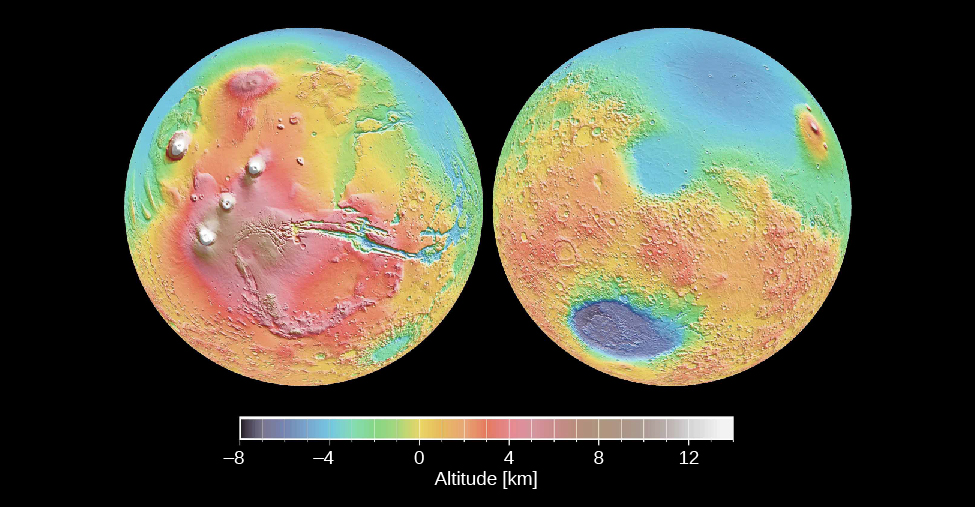

Mars map from laser ranging

These globes are highly precise topographic maps, reconstructed from millions of individual elevation measurements made with the Mars Global Surveyor. Color is used to indicate elevation. The hemisphere on the left includes the Tharsis bulge and Olympus Mons, the highest mountain on Mars. The hemisphere on the right features the Hellas basin, which has the lowest elevation on Mars.

The next four planets (Jupiter through Neptune) are much larger and are composed primarily of lighter ices, liquids, and gases. We call these four the jovian planets (after “Jove,” another name for Jupiter in mythology) or giant planets— a name they rightfully deserve. These planets do not have solid surfaces on which future explorers might land. They are more like vast, spherical oceans with much smaller, dense cores.

The giant planets are very far from the Sun. Jupiter is more than five times farther from the Sun than Earth’s distance (5 AU), and takes just about 12 years to make one full lap around the Sun. Saturn is about twice as far away as Jupiter (almost 10 AU) and takes nearly 30 years to complete one orbit. Uranus orbits at 19 AU with a period of 84 years, while Neptune, at 30 AU, requires 165 years for each trip around the Sun. These long timescales make it difficult for us short-lived humans to study seasonal change on the outer planets.

| Basic Properties of the Jovian Planets | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planet | Distance

(AU) |

Period

(years) |

Diameter

(km) |

Mass

(Earth = 1) |

Density

(g/cm3) |

Rotation

(hours) |

| Jupiter | 5.2 | 11.9 | 142,800 | 318 | 1.3 | 9.9 |

| Saturn | 9.5 | 29.5 | 120,540 | 95 | 0.7 | 10.7 |

| Uranus | 19.2 | 84.1 | 51,200 | 14 | 1.3 | 17.2 |

| Neptune | 30.0 | 164.8 | 49,500 | 17 | 1.6 | 16.1 |

Jupiter

Jupiter

Jupiter, the giant among giants, has enough mass to make 318 Earths. Its diameter is about 11 times that of Earth (and about one tenth that of the Sun). Jupiter’s average density is 1.3 g/cm3, much lower than that of any of the terrestrial planets. (Water has a density of 1 g/cm3.) Jupiter’s planetary material is spread out over a volume so large that more than 1,400 Earths could fit inside it.

Seen through a telescope, Jupiter is a colorful and dynamic planet. Distinct details in its cloud patterns allow us to determine the rotation rate of its atmosphere at the cloud level, although such atmosphere rotation may have little to do with the spin of the underlying planet. The vibrant colors of the clouds on Jupiter present a puzzle to astronomers: given the cool temperatures and the composition of nearly 90% hydrogen, the atmosphere should be colorless. One hypothesis suggests that perhaps colorful hydrogen compounds rise from warm areas.

The challenges of exploring so far away from Earth are considerable. Flight times to the giant planets are measured in years to decades, rather than the months required to reach Venus or Mars. Even at the speed of light, messages take hours to pass between Earth and the spacecraft. If a problem happens near Saturn, for example, you can't wait hours for the alarm to reach Earth and for instructions to be routed back to the spacecraft. Spacecraft to the outer solar system must therefore be highly reliable and capable of a greater degree of independence and autonomy. Outer solar system missions also must carry their own power sources since the Sun is too far away to sufficient solar energy. Heaters are required to keep instruments at proper operating temperatures, and spacecraft must have radio transmitters powerful enough to send their data to receivers on distant Earth.

The first spacecraft to investigate past Mars were the NASA Pioneers 10 and 11, launched in 1972 and 1973 as pathfinders to Jupiter. One of their main objectives was simply to determine whether a spacecraft could actually navigate through the belt of asteroids that lies beyond Mars without getting destroyed by collisions with asteroidal dust. Another objective was to measure the radiation hazards in the magnetosphere of Jupiter. Both spacecraft passed through the asteroid belt without incident, but the energetic particles in Jupiter’s magnetic field nearly wiped out their electronics, providing information necessary for the safe design of subsequent missions.

Pioneer 10 flew past Jupiter in 1973, after which it sped outward toward the limits of the solar system. Pioneer 11 undertook a more ambitious program, using the gravity of Jupiter to aim for Saturn, which it reached in 1979. The twin Voyager spacecraft launched the next wave of outer planet exploration in 1977. Voyagers 1 and 2 each carried 11 scientific instruments, including cameras and spectrometers, as well as devices to measure the characteristics of planetary magnetospheres. Since they kept going outward after their planetary encounters, these are now the most distant spacecraft ever launched by humanity. 🛰️

Saturn

Saturn

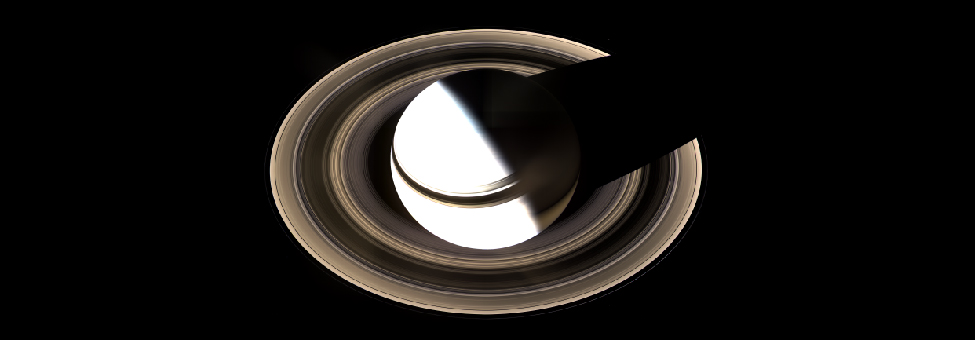

Saturn, the sixth planet from the Sun, is famous for its extensive ring system. It's the second-largest planet in our solar system.

The atmosphere of Saturn is made of approximately 75% hydrogen and 25% helium, with trace amounts of methane, ethane, propane, and other hydrocarbons. The overall structure is similar to that of Jupiter. Temperatures are somewhat colder, however, and the atmosphere is more extended due to Saturn’s lower surface gravity. Thus, the layers of the atmosphere are stretched out over a larger distance.

Saturn has one anomalous cloud structure that has mystified scientists: a hexagonal wave pattern around the north pole. The six sides of the hexagon are each longer than the diameter of Earth. Winds are also extremely high on Saturn, with speeds of up to 1,800 kilometers per hour measured near the equator. This makes the formation of the hexagon even more unusual.

The image below shows Saturn and its complex system of rings, taken from a distance of about 1.2 million kilometers. This natural-color image is a composite of 36 images taken over the course of 2.5 hours by Cassini.

Uranus

Uranus

Uranus is the seventh planet from the Sun and has a unique blue-green color due to methane in its atmosphere. It rotates on its side, making it unique among the planets.

We don’t know what caused Uranus to be tipped over like this, but one possibility is a collision with a large planetary body when our system was first forming. Whatever the cause, this unusual tilt creates dramatic seasons.

The planet Uranus is named after the ancient Greek God of the heavens, the earliest supreme god. He was the father of Cronus / Saturn, who was the father of Zeus / Jupiter.

Both Uranus and Neptune are blue because they have methane. Uranus is larger in size than Neptune but it is smaller in weight. It has thirteen ring systems and 23 confirmed moons.

Uranus has thirteen distinct ring systems thought to have formed about 600 million years ago from the collision of possible other moons or big objects. The rings around Uranus are unique since they aren’t bright like the ones of Saturn, and they are extremely narrow. With this low albedo they appear as black as charcoal. The widest of the rings is called the epsilon ring, spreading from 20 to 100 kilometers wide.

In 2033, Uranus will complete its third orbit around the sun since its discovery in 1781. The planet returned to the point of its discovery twice since then, in 1862 and 1943, one day later each time.

Neptune

Neptune

Neptune is the eighth and farthest known planet from the Sun in our solar system. It's known for its deep blue color and strong winds, some of the fastest in the solar system.

Neptune differs from Uranus in its appearance, although their basic atmospheric temperatures are similar. The upper clouds are composed of methane, which forms a thin cloud layer near the top of the troposphere. Most of the atmosphere above this level is clear and transparent, with less haze than Uranus. The scattering of sunlight by gas molecules lends Neptune a pale blue color similar to that of Earth’s atmosphere. Another cloud layer, perhaps composed of hydrogen sulfide ice particles, exists below the methane clouds.

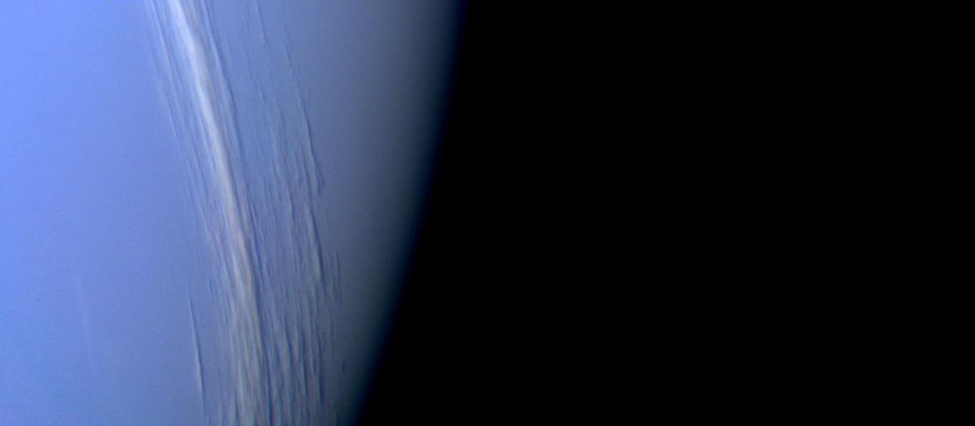

High Clouds in the Atmosphere of Neptune

These bright, narrow cirrus clouds are made of methane ice crystals. From the shadows they cast on the thicker cloud layer below, we can measure that they are about 75 kilometers higher than the main clouds.

The Four Giant Planets

The outer solar system contains the four giant planets: Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. The gas giants Jupiter and Saturn have overall compositions similar to that of the Sun. These planets have been explored by the Pioneer, Voyager, Galileo, and Cassini spacecraft. Voyager 2, perhaps the most successful of all space-science missions, explored Jupiter (1979), Saturn (1981), Uranus (1986), and Neptune (1989)—a grand tour of the giant planets—and these flybys have been the only explorations to date of the ice giants Uranus and Neptune. The Galileo and Cassini missions were long-lived orbiters, and each also deployed an entry probe, one into Jupiter and one into Saturn’s moon Titan.

Other major bodies

Pluto

Pluto

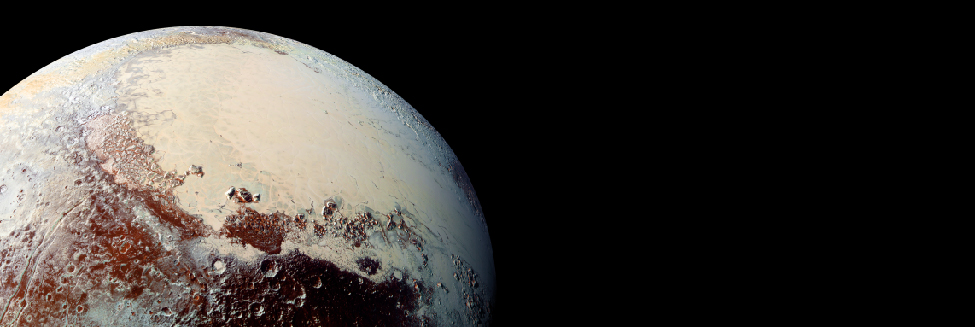

Pluto Close-up

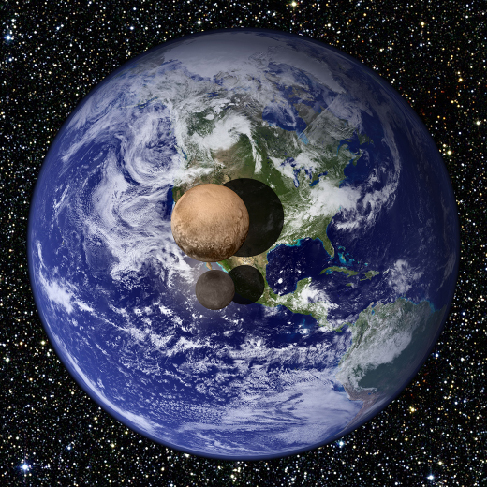

Pluto is not a moon, but its size and composition are similar to many moons in the outer solar system. Our understanding of Pluto (and its large moon Charon) have changed dramatically as a result of the NASA New Horizons flyby in 2015.

From the time of its discovery, it was clear that Pluto was not a giant like the other four outer solar system planets. For a long time, it was thought that the mass of Pluto was similar to that of Earth, so it was classified as a fifth terrestrial planet, somehow misplaced in the far outer reaches of the solar system. There were other anomalies, however, as Pluto’s orbit was more eccentric and inclined to the plane of our solar system than that of any other planet. Only after the discovery of its moon Charon in 1978 could the mass of Pluto be measured, and it turned out to be far less than the mass of Earth.

This graphic vividly shows how tiny Pluto (and its Moon Charon) is relative to a terrestrial planet like Earth. That is the primary justification for putting Pluto in the class of dwarf planets rather than terrestrial planets.

In addition to Charon, Pluto has four small moons. Subsequent observations of Charon showed that this moon is in a retrograde orbit and has a diameter of about 1200 kilometers, more than half the size of Pluto itself. This makes Charon the moon whose size is the largest fraction of its parent planet. We could even think of Pluto and Charon as a double world (Tatooine?). Seen from Pluto, Charon would be as large as eight full moons on Earth.

To many astronomers, Pluto seemed like it just didn't fit in with the rest of the planets. Neither its path around the Sun nor its size resembles either the giant planets or the terrestrial planets. In the 1990s, astronomers began to discover additional small objects in the far outer solar system, showing that Pluto was not alone after all. One of these objects, called Eris, is nearly the same size as Pluto and another, Makemake, is substantially smaller. It became clear that Pluto was so different from the other planets that it needed a new classification. Therefore, it was called a dwarf planet, meaning a planet much smaller than the terrestrial planets. We now know of many small objects in the vicinity of Pluto and several have been classified as dwarf planets.

A similar history was associated with the discovery of the asteroids. When the first asteroid (Ceres) was discovered at the beginning of the nineteenth century, it was hailed as a new planet. In the following years, however, other objects were found with similar orbits to Ceres. Astronomers decided that these should not all be considered planets, so they invented a new class of objects, called minor planets or asteroids. Today, Ceres is also classified as a dwarf planet. Both minor planets and dwarf planets are part of a whole region of similar objects.

This intriguing image from the New Horizons spacecraft, taken when it flew by the dwarf planet in July 2015, shows some of its complex surface features. The rounded white area is temporarily being called the Sputnik Plain, after humanity’s first spacecraft.

| The Planets | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Distance from Sun

(AU) |

Revolution Period

(y) |

Diameter

(km) |

Mass

(1023 kg) |

Density

(g/cm3) |

| Mercury | 0.39 | 0.24 | 4,878 | 3.3 | 5.4 |

| Venus | 0.72 | 0.62 | 12,120 | 48.7 | 5.2 |

| Earth | 1.00 | 1.00 | 12,756 | 59.8 | 5.5 |

| Mars | 1.52 | 1.88 | 6,787 | 6.4 | 3.9 |

| Jupiter | 5.20 | 11.86 | 142,984 | 18,991 | 1.3 |

| Saturn | 9.54 | 29.46 | 120,536 | 5686 | 0.7 |

| Uranus | 19.18 | 84.07 | 51,118 | 866 | 1.3 |

| Neptune | 30.06 | 164.82 | 49,660 | 1030 | 1.6 |

Smaller members of the solar system

Most of the planets are accompanied by one or more moons- only Mercury and Venus travel through space alone. There are more than 180 known moons orbiting planets and dwarf planets, and undoubtedly many other small ones remain undiscovered. The largest of the moons are as big as small planets and just as interesting. In addition to our Moon, they include the four largest moons of Jupiter (called the Galilean moons, after their discoverer) and the largest moons of Saturn and Neptune (somewhat confusingly named Titan and Triton).

Each of the giant planets also has rings made up of countless small bodies ranging in size from mountains to mere grains of dust, all in orbit around the equator of the planet. The bright rings of Saturn are, by far, the easiest to see. They are among the most beautiful sights in the solar system. All ring systems are interesting in their own way because of their complicated forms, influenced by the pull of the moons that also orbit these giant planets.

Asteroid Eros

This image of an asteroid was taken by the NEAR-Shoemaker spacecraft from an altitude of about 100 kilometers. The view of the heavily cratered surface is about 10 kilometers wide. This spacecraft orbited Eros for a year before landing gently on its surface.

Another class of small bodies is composed mostly of ice, made of frozen gases such as water, carbon dioxide, and carbon monoxide; these objects are called comets. Comets also are remnants from the formation of the solar system, but they were formed and continue (with rare exceptions) to orbit the Sun in distant, cooler regions—stored in a sort of cosmic deep freeze. This is also the realm of the larger icy worlds, called dwarf planets.

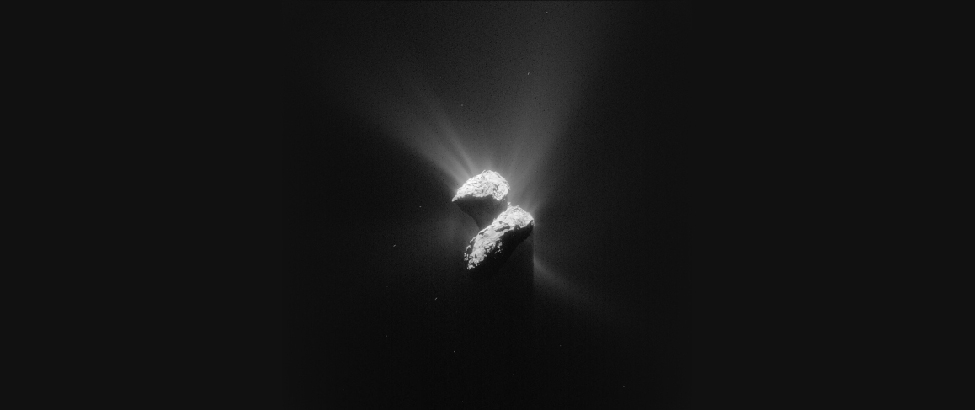

Comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko (67P)

This image shows Comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko, also known as 67P, near its closest approach to the Sun in 2015, as seen from the Rosetta spacecraft. Note the jets of gas escaping from the solid surface.

Finally, there are countless grains of broken rock, which we call cosmic dust, scattered throughout the solar system. When these particles enter Earth’s atmosphere (as millions do each day) they burn up, producing a brief flash of light in the night sky known as a meteor (meteors are often referred to as shooting stars). Occasionally, some larger chunk of rocky or metallic material survives its passage through the atmosphere and lands on Earth. Any piece that strikes the ground is known as a meteorite. (You can see meteorites on display in many natural history museums and can sometimes even purchase pieces of them from gem and mineral dealers.)

TL;DR

Our solar system currently consists of the Sun, eight planets, five dwarf planets, nearly 200 known moons, and a host of smaller objects. The planets can be divided into two groups: the inner terrestrial planets and the outer giant planets. Pluto, Eris, Haumea, and Makemake do not fit into either category; as icy dwarf planets, they exist in an ice realm on the fringes of the main planetary system. The giant planets are composed mostly of liquids and gases. Smaller members of the solar system include asteroids (including the dwarf planet Ceres), which are rocky and metallic objects found mostly between Mars and Jupiter; comets, which are made mostly of frozen gases and generally orbit far from the Sun; and countless smaller grains of cosmic dust. When a meteor survives its passage through our atmosphere and falls to Earth, we call it a meteorite. ☄️